The Climber

This story appears in the July 2014 issue of Packerland Pride magazine. Subscribe to the magazine here.

—

There are plenty of ways to explain him, to describe him as we’ve grown to see him over his almost-always-open, consistent, memorably out-of-nowhere career at Wisconsin.

He was a would-be track athlete before he decided on football, a walk-on scout team quarterback who turned enough heads to try wide receiver. After he forced his hands to catch almost anything thrown his way, working years of rust off his fingertips. All of that was before he earned a scholarship following three seasons in Madison, before he became one of the Badgers’ most dependable downfield targets in recent memory. He won receiver-cornerback battles with route-running as specific as a Congressional subcommittee (but more productive), with speed and separation mixed with an understanding of where to be and how to get there, those unknown-but-obvious traits that accompany a receiver who just makes catches, again and again. There are all those attributes that describe who he is as a wideout. We see them clearly.

To watch him on Saturdays was to highlight just how uniquely talented he was, to see what was separating him away from the norm, to realize how singularly determined he must be to simply keep working on what worked, then go to work on defenses. Letting everyone else sit around and wonder how it was happening.

Jared Abbrederis, the football player, is the guy who’s improved since he started, and still is. Jared Abbrederis, the guy with the LinkedIn profile listing Team Member with the University of Wisconsin Football Team on his online resume, the guy from Wautoma – a small city about an hour and a half to the southwest of Green Bay – is just Jared to anyone knows him. He could be so many people I went to college with in Central Wisconsin. Abbrederis is familiar in that way people you don’t know can sometimes appear. He’s the guy who probably played sports in high school now out for $1 bottles of beer at Partner’s on Wednesday night. He’s one of the guys in that Intro To 100-level class. I think I remember seeing that guy on the sidewalk.

He seems familiar. But then you remember why you really remember him: for playing wide receiver unassumingly better for so long at Wisconsin his numbers no longer matched the easily-applied underdog label initially given to him. Abbrederis finished first in career catches (202), second in receiving yards (3,140) and touchdown receptions (23) for the Badgers.

You couldn’t underrate what he was doing even if he was still somehow “underrated” to the general public. But time went on. The list of those who didn’t know his game shrank (Hi, Bradley Roby!) and shrank, until Abbrederis was an underdog for motivational purposes and easy headlines only. One cannot win, beat as many defenders, come out a few steps or inches ahead as many times as he has, and be an underdog at that level. If people passed on or overlooked him, if his combine results deterred some NFL teams and those brave anonymous scouts, well, using the underdog trope doesn’t very well mask a mistake.

––––––

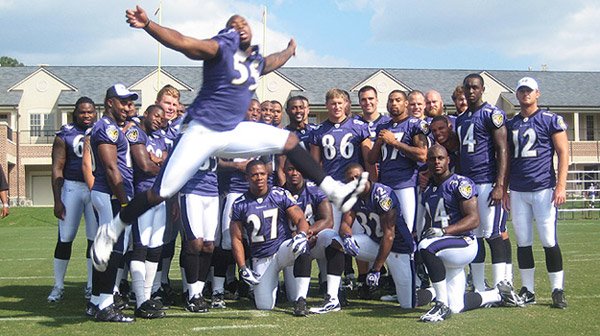

The Green Bay Packers selected him in the fifth round of the 2014 NFL Draft. The Packers taking a Badger, Ted Thompson’s first of his tenure, was one of those legitimately surprising sports moments dotting the landscape every so often like faraway deer in a field. The valley between what you would like to happen and what actually does rarely offers such easy accessibility between former and latter. Keeping Abbrederis in-state was installing a high-speed moving walkway over the crevasse.

For Abbrederis himself it is the next step on a staircase of doubt-shattering and goal-achieving. A chain of events that, even through the eyes of someone as notedly modest as Abbrederis, can’t be seen as anything less than unbelievable. When a former coach suggests the story has the makings of a movie, he isn’t shooting for the stars. They’ve already seen it in Wautoma. It’s about Jared Abbrederis, but this is about him through some of the people who knew him as this was just getting started, and before Packers training camp, as that process starts all over. Unlike the man himself, they are glad to talk about Jared Abbrederis.

––––––

As you approach the high school, orange and black Wautoma Hornets lawn signs stick out amongst green along the road. The school sprawls, the gymnasium to the right, the main entrance and auditorium on the left. In the back there’s ongoing construction. They’re getting new workout facilities. The football team is getting new lockers, the kind you can sit inside.

Towards the gym Abbrederis memorabilia starts showing up on the walls. High school honors and state titles. Facing the gym doors hangs a framed red No. 4 Badgers jersey and receiving gloves.

Jared Abbrederis is an imaginary figure to younger football players who’ve spent Saturdays watching him play, knowing he came from the same place. He is “just Jared”, as current Wautoma head football coach Mike Klieforth says, to those who know him. But even those who know him or coached him or know his family or simply watched him in high school and at Wisconsin, they all are coming to terms, still processing, the fact that Abbrederis will attend training camp in Green Bay this summer.

––––––

Dave Woyak, Wautoma offensive coordinator and quarterbacks coach, will never forget the moment during Wautoma’s run to the Division 4 state championship in 2008. It was the first round of the playoffs, Wautoma hosting Xavier. The two teams went back and forth all night, and went to overtime tied at 32. High school football runs a variation of college football overtime rules, each team getting a chance to score from deep inside their opponent’s territory, going back and forth until a winner’s decided. The teams traded touchdowns and extra points in the first frame. Xavier led off the second with another touchdown, another extra point.

Abbrederis ran in a touchdown to pull Wautoma within one.

“There was a feeling that everyone wanted to wrap it up here,” Woyak says of the moment.

Wautoma’s coaching staff decided to go for two.

Their entire season hinging on the next play, Woyak came out to the huddle with the play call, prepared for anything. Prepared to settle nerves or hear ideas, prepared to change the call depending on the team’s reaction.

The play was meant to be simple, one they’d run plenty of times before. Still, Woyak wasn’t sure what the mood would be with so much on the line.

He arrived at the huddle. Woyak remembers it clear as day: the entire offense looked up calmly at him, relaxed in the moment, and listened to the play call.

“They said, ‘Okay’, lined up, and ran it perfectly,” Woyak says. It was a play-action fake. Abbrederis rolled to his right, completing the pass for the Wautoma win.

“That was the aura of the team for that whole postseason run,” Woyak says.

All quiet calm, a subliminal awareness of where they were going and what they were going to achieve that season. That this is as good a way as any to describe their senior quarterback that season is no small coincidence.

––––––

Woyak teaches elementary school a few turns down the road from the high school. A Wautoma native, he began working one-on-one with Abbrederis his freshman year in high school. Their specialities lined up perfectly: Woyak the offensive coordinator/quarterbacks coach and the track and field coach working with hurdlers in particular. Abbrederis the smoothly athletic kid starting his high school sports career.

His athletic abilities got Abbrederis noticed early. Woyak remembers when he, as a freshman, tried hurdling for the first time. He cleanly breezed over one hurdle after another. They stacked a couple and Abbrederis cleared those too. “He was a natural, a natural athlete,” Woyak says.

In 2006, his sophomore year, Abbrederis became Wautoma’s starting quarterback, the most important position usually reserved for the offense’s biggest threat. Abbrederis’s class was starting to attract attention in the community because of their work ethic. His quiet leadership was honed there as an underclassman. Already, he was nifty enough to make people miss, Woyak says.

But Abbrederis’s season was cut short after a vicious combination of high and low hits bent him, breaking his femur, starting him on a ridiculously quick path to recovery. The team finished 6-3 overall, good enough to host two playoff games in what was their first playoff appearance in three years.

It was the beginning of a sea change for Wautoma football. Klieforth remembers about 150 people showing up for that second playoff game on a Saturday afternoon. The next year, with Abbrederis back at quarterback, the Hornets finished 10-2 overall, losing in the third round of the playoffs. But by then they had a traveling section of fans around a thousand strong. It was from this deep, talented, hard-working class that Abbrederis came from first. They were loved in the community. Before they would eventually be on the map thanks to Abbrederis’s collegiate exploits, Wautoma got its home-field advantage back first.

When Abbrederis broke his leg as a sophomore, Woyak says he just started working away, tirelessly rehabbing day after day until he was ready for track and field in the spring. After an understandably slow start to the season, he finished in the top 10 in four different events at the spring state track and field meet.

“He just outworks everybody,” says Dennis Moon, Abbrederis’s head football coach at Wautoma and 2011 inductee to the Wisconsin Football Coaches Association Hall of Fame. “The biggest thing is his work ethic.”

––––––

“If you would’ve asked me that back in high school, I would definitely have said, ‘No, I’ve seen other guys like him before,’” Moon says when asked if he thought he’d ever see Abbrederis as a professional football player.

Moon saw the athletic gifts Abbrederis possessed but he’d seen those in players before. But combine those and a relentless drive and an unendingly unending hunger to be better, faster, smarter, stronger? A mindset that’s never satisfied with a next step? That’s when you might get someone special.

“When he was in high school he was a pretty good athlete, but there’s a lot of really good athletes in high school that never take it to the whole next level,” Moon says. “He trained unbelievably hard in high school. That’s a thing a lot of people don’t realize. The kid was a weight room crazy man, his intensity when he worked – you can tell when kids nowadays go lift weights, they go through the motions and they lift their weights – but he was intense. He had a purpose in mind every time he went in the weight room.”

As a senior Abbrederis and the Hornets ascended into a full-blown force. Throwing about a quarter of the time, much of the offense relied on a running game where Abbrederis took what the defense gave him, either handing the ball off or turning upfield himself. He continued making people miss at a high clip.

“There were times when we had, and we were pretty good, but there’d still be three or four guys that went unblocked and went to tackle him, and he just made them miss,” Moon says. “That’s when I first (thought), you know, this guy’s got some moves. And just like the pros (after college), we were always wondering after high school, ‘Boy, is he big enough to play Division 1 football?’ He proved everybody wrong.”

––––––

There are all the stories of his feats of strength or freakish spurts of athleticism. There’s the day in practice he was chatting with Woyak, playing catch, when a pass was sailed back his way. Abbrederis shot up from his flat-footed stance, snaring the ball with one hand, landing back on earth like it hadn’t happened.

“I told him right there he might have to be a wide receiver,” Woyak says.

There was the state semifinal game in ‘08 where Baldwin-Woodville couldn’t stop Abbrederis from tearing them up on the ground. So Wautoma kept running him, running him again and again until his final line in a 42-24 win was 38 carries, 264 yards, three rushing touchdowns and one passing score.

“Most kids that are 175 pounds, taking beatings like that, like a fullback or a tailback, they don’t normally do that kind of stuff,” Moon says. “He’s just tough. His toughness was never a question, and I think that transitioned over to blocking. He wasn’t afraid to stick his nose in there, go inside and crack a linebacker, block on the outside.”

Moon says his long strides as a runner, previously developed as a hurdler, eased his transition to wide receiver at Wisconsin. He glides by defenders not with a sprinter’s speed or obvious, Sam Shields-ian feet of fire, but in an easy way. He’s on top and by you before you know what happened. And when he gets the ball he’s always been nifty enough to make you miss.

In one of his first interviews after a Packers OTA practice earlier this summer, Abbrederis mentioned learning the playbook from all positions. It’s a task that makes mastery all the more difficult, but also the way he’s comfortable learning from his days as a quarterback. This wide-angle view of an offense has made him a smarter player and is paying off as a wideout.

“He just understands what the concepts are,” Moon says. “As a quarterback he had to know what everybody’s doing out there, and I think that helps so much now transferring over to receiver because now he can understand why you’re doing what you’re doing, each decision, how I can fit in here. I think that made it a really easy transition. Whereas if he just grew up around wide receivers his whole life then you just know your position.”

And joining every one of those stories is his modesty in a small town where he was the star quarterback of the football team demolishing everyone. Anyone you talk to about Abbrederis sings a similar verse: Hard working, great kid, incredible work ethic, constantly trying to learn, making Wautoma proud because of the representative he is of his hometown.

Woyak says he was a great teammate in high school. Others wanted to play for him.

“He always stayed with the offense and made the plays, the right plays, based on what the situation called for,” Woyak says.

During blowouts his senior year (of which there were a few), Abbrederis would be pulled early. He’d leave without complaint and stand on the sidelines cheering on his teammates. Always involved in the game. Abbrederis scored 28 points himself for Wautoma’s 2009 state champion track and field team. Afterwards he pointed to teammates who scored five or six total as the real reasons they won.

“Everybody knew he was pretty good but he was one of the most humble guys on the team, one of the most humble guys you’ve ever met,” Moon says. “He never took credit for anything. With his faith, he always gave God credit for everything; he was never ‘look at me,’ that kind of thing.

“I think that’s what makes players around him want to play, raise their level too. They say, ‘Jeez, look at this kid.’ And Madison coaches have said that too. He’s out there sweating every day. They say, ‘Hey, you don’t have to do these reps,’ and he’s fighting out there every day and he’s taking the reps because it’s like he’s trying to win that position every chance, every practice. That’s the thing that just drives it.”

––––––

Woyak remembers talking to Abbrederis during his first season with the Badgers. Abbrederis was frustrated about being redshirted, about not playing a major role on a team for the first time, well, ever. He was a scout team quarterback playing the role of other people. After that season he did what he’d always done to that point, whenever something threatened to derail the only direction he allowed for himself. He stayed in Madison for the summer. He worked out with the wide receivers. He called quarterbacks and offered to run routes.