Six games, none to go: When the Packers won to clinch the division with no games left on the schedule

This story appears in the December 2014 issue of Packerland Pride magazine. Subscribe to the magazine here.

—

The last game of the 2014 regular season could have a lot on the line. It could, at its lowest point of tension, just be the opportunity to not be swept by the Detroit Lions in a year. It could be the difference between NFC North division champion and second place. It could be the difference between the postseason and an early end.

The Green Bay Packers have clinched the division crown six other times, along with two decided technically after the regular season, in their history in the final game of the season. This is a look at those games, all with stakes about as high and as late into the games each team is promised as possible. Since we’re only talking about division clinchers, you know they’re all happy endings. If that is the situation come Week 17 of this year, we’ll be hoping for one more. We’ll start with the two postseason clinchers.

December 4, 1938, and December 26, 1965.

Despite losing back-to-back games in the regular season finale and NFL Championship game to the New York Giants, the Packers won the Western Division title in 1938 thanks to a strong beginning and middle of their season. The Packers dropped one apiece to the Lions and Chicago Bears, the latter a frightening 2-0 loss played during a Green Bay downpour, but otherwise finished without another divisional defeat. Green Bay waited its way to a title, finishing their 8-3 campaign on November 20 while Detroit, then 6-3, still had two games to go. They would split, losing their December 4 finale to the Philadelphia Eagles to finish 7-4, effectively clinching the then fifth division title for the Packers.

Green Bay earned the difficult three-game sweep of a single team in season in 1965, defeating the Baltimore Colts in Weeks 2 and 13, and a final time in a 13-10 overtime win on December 26 that doubled as a playoff to decide who’d face the Cleveland Browns in the NFL Championship after both teams finished the regular season with matching 10-3-1 records.

The day after Christmas 1965 was cold in Green Bay with a wind chill of about 12 degrees. After scoring on a fumble return the Colts took a 10-0 lead into halftime. Paul Hornung plunged in from a yard out to give the Packers their only touchdown in the third, and Don Chandler booted a 22-yarder in the fourth to tie, then a 25-yard field goal to win in overtime. Green Bay’s defense, as it had for much of the season, carried an average offense and also overcame four turnovers on this day, allowing only nine first downs and 175 total yards to the Colts. The Packers won the West, and, thanks to one more dominating lockdown by the defense, went on to capture the NFL title with a 23-12 win over Cleveland.

December 3, 1939.

Before the Packers’ fifth world title, a 27-0 wipeout of the Giants, they had to hold off the Chicago Bears in a sprint for the West crown. Curly Lambeau’s squad beat the Bears in Green Bay in Week 2, Chicago returning the favor at home with a 30-27 win in Week 8. From there, no longer able to settle the matter head-to-head, the teams started running on parallel lines to the same spot, each winning three straight heading into the regular season finale. Chicago’s fate was in the hands of their rivals, however, because of a two-game losing streak in late October, their 10-0 home loss to the Lions ultimately proving the costliest despite beating the Packers the following week. Because of their slip against Detroit, it was Green Bay’s division to win or lose.

So, fittingly, in Detroit’s Briggs Stadium, the Packers grounded out a 12-7 victory, scoring on a short 16-yard field goal by Tiny Engebretsen, a safety on a blocked punt, and the winner, a 1-yard touchdown run by Clarke Hinkle in the final frame.

At 9-2 the Packers finished in the top five statistically in both points scored and allowed, and only percentage points behind the Giants (9-1-1) for the league’s best record. Of course, they corrected this in the title game, scoring 20 second half points and notching the first-ever shutout in a championship game, on the Wisconsin State Fair Park grounds.

December 17, 1960.

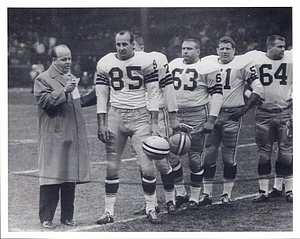

In 1960 Bart Starr claimed the starting quarterback job for good and the Packers, in Vince Lombardi’s second season as head coach, reached the NFL title game for the first time since 1944. It was a formative year for what would become of the 1960s, especially after the season ended in losing in the NFL Championship to the Eagles, a thing Lombardi promised wouldn’t happen again during his time in Green Bay.

But before they could lose the game that further fueled the engine in Lombardi’s one-direction mind, the Packers had to survive a competitive West division. After nine games the Packers and San Francisco 49ers were 5-4, the Lions 4-5. The Colts were 6-3, the Bears 5-3-1. From that point on Baltimore and Chicago lost their last six collective games, quickly collapsing from in control to out of contention.

Heading into the final week the Packers were 7-4, coming off a 13-0 win on the road over San Francisco, dropping the Niners to 6-5 and an arm’s reach away. The Lions were finishing strong, reeling off four consecutive wins to end their regular season at 7-5, but still remained in the hole they’d dug for themselves after losing the first three games of the season. It came down to the Packers and Los Angeles Rams in the Coliseum. And in a chippy contest, the Packers, with Bart Starr’s devastating precision (8-of-9 passing for 201 yards and two touchdowns) and a defense that forced four turnovers, won 35-21, outscoring the Rams 21-0 in the decisive second quarter, to claim the division. Green Bay got long touchdown catches from Max McGee and Boyd Dowler, a short scoring run by Hornung, and a Carroll Dale touchdown reception in the fourth for crucial breathing room when Los Angeles was making a late push.

December 16, 1962.

Truth be told the West division was sealed before the Packers made a single play on this day. But, considering how close Green Bay was to perfection in 1962 in nearly every phase and facet of the game, it feels right that the division title would come that easy, and that they’d still win their finale anyway.

Green Bay led the league in scoring at nearly 30 points a game, also setting the pace defensively, allowing just over 10 points per contest. They forced turnovers, ran with Jim Taylor (who finished with 1,474 rushing yards and 19 touchdowns) and Paul Hornung (who missed part of the year with a knee injury), and threw with Starr (12 touchdowns, 9 interceptions, and 2,438 yards) when they felt like changing it up. Their only blemish in ‘62 was a disastrous Thanksgiving Day in Detroit where they fell behind 26-0 and couldn’t rally, falling 26-14. Starr was sacked 10 times and threw two picks.

The Lions entered the final week 11-2, but paved the easy way for the Packers division title thanks to a 3-0 loss to the Bears. By the time Green Bay started against the woeful Rams in Los Angeles later that day, the title was theirs. But because this was a football game and they were coached by Lombardi, the Packers did enough to earn a 20-17 win, scoring on touchdowns from tight end Ron Kramer, Taylor – who broke the then-single season touchdown record with No. 19 – and an 83-yard catch-and-run by Hornung.

Green Bay beat the Giants 16-7 in the championship, cementing one of the most dominant seasons in team history with a rightful title.

December 24, 1995.

The Packers hadn’t been division champions since the strike-shortened 1982 season. On Christmas Eve of ‘95, a gift from the enemy would make sure that changed.

The NFC Central was tough that year. Only one team finished under .500 and just barely, with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers at 7-9. Green Bay and Detroit split their regular season series, but at 10-5 to the Lions’ 9-6, the Packers could avoid the hassle and clinch the division outright with a win over the Pittsburgh Steelers. The Steelers were winners of eight straight heading into their Week 17 meeting in Lambeau Field, and made a long title run in the postseason before losing in the Super Bowl to the Dallas Cowboys.

Green Bay, behind two touchdown passes from Brett Favre, who’d win his first Most Valuable Player award that year, held an 11-point second half lead, but could never shake the Steelers, who were only playing against the game with home-field advantage wrapped up for the playoffs. Leading 24-19 with 16 seconds left to play, it came down to a fourth down. The Packers defense trying to hang on at their own 6-yard line. Pittsburgh quarterback Neil O’Donnell found a completely wide open Yancey Thigpen in the back of the end zone, and for the moment the ball was in the air it appeared the game was over. It was, but not in the way everyone thought. Thigpen made a slight adjustment and couldn’t handle the pass, the ball slipping through his hands and bouncing out of bounds after hitting his knee on a second attempt to corral it, sealing the division and playoff berth for the Packers, who’d go all the way to the NFC Championship game. One of those classic Lambeau Field moments.

(Side note: This is one of our first truly-and-still vivid memories of watching a Packers game growing up. We were 8, and we remember the shock of seeing something happen that so often does not, a wide open receiver dropping a usually-routine catch, and how it could happen at that time of all times, when we needed it most. We remember the snow falling, celebrating with our brother and the babysitter, and then again when our parents, who’d went to the game, got back home. This was one of, if not the, first instances where we began internalizing that anything can happen in sports and at any time; that chaos, as we learned again in this next game, is always a play away.)

December 28, 2003.

The second of Green Bay’s back-to-back-to-back NFC North division titles under Mike Sherman seemed like a longshot midway through the year. The Packers were 4-5 and the Minnesota Vikings, through those same 10 weeks, were 6-3. In a down year in the North, it was down to these old foes, and the year ended not with them together but joined forever, and with the appropriate amount of thrills, insanity, and general ridiculousness found common in Green Bay during those strange Sherman seasons.

Despite the start the Packers were reeling off wins down the stretch. They entered Week 17 against the Denver Broncos, who had already clinched a playoff berth, on the heels of Favre’s mystical wonder-game against the Oakland Raiders on Monday Night Football a day after the sudden death of his father. To say the stars seemed to be aligning over Green Bay would be an understatement, and yet, Minnesota could still win the division with a victory over the lowly Arizona Cardinals.

The rivals played at the same time but across the country from one another. Denver was content to take the loss in Green Bay, but as the Packers were rolling to a 31-3 romp, the Vikings were leading in the desert, 17-6, with 6:52 left in the game.

And then spectacularly and hilariously, as the Lambeau Field crowd and the Packers monitored the proceedings on the video boards, Arizona rallied. They scored with two minutes to go but didn’t get the two-point conversion, meaning they’d have to score another touchdown. Then the Cardinals recovered the ensuing onside kick. We feel it’s important to say this here: At this point the Vikings were sort of inviting something terrible to happen, because the same type of stuff that happens to people who make fun of or doubt evil spirits in horror movies starts happening to them here. Two Vikings go up for that onside kick and cancel each other’s chances at catching it out. That’s the only reason Arizona gets the ball back.

This is the Cardinals’ first play from scrimmage: From their own 39 quarterback Josh McCown takes the snap from the shotgun, drops back and stumbles on nothing. He gets his footing back to about a 40 percent operating clip and flings the ball downfield before he gets hit. This deeply broken, aimless play yields the Cardinals 30 yards on a defensive pass interference penalty. Either Minnesota did not believe in ghosts or were beginning to become resigned to their tormented fates.

Then McCown is hit and stripped on third down. A Cardinals lineman recovers to keep the game alive while the clock is running. Arizona scrambles to get a fourth-and-freaking-24 off before time runs out. They can’t even get into a huddle on this play, and we can’t stress chaos’s impact on the whole situation enough. McCown gets out of the pocket and finds time on the right side of the field, throwing a dart to receiver Nate Poole in the corner of the end zone. Poole only gets one foot in bounds, but because of the league’s rules at the time, a force out is not incomplete like it is today. Minnesota had really upset the wrong demons, here. Touchdown, Cardinals. No time on the clock.

The Packers won the North on that play, and we can’t remember a non-Packers outcome that we’ve ever loved more.

December 29, 2013.

This one you may recall. Thanks to a folly of missed chances and badly stubbed toes down the stretch, the Lions and Bears closed the door to the NFC North and, thinking they were in a safe neighborhood, neglected to lock it. In Week 17 Aaron Rodgers, Randall Cobb, and the Packers slipped in, Detroit was passed out in a chair, and before Chicago realized the threat was inside, Green Bay stole the division title and took the Bears’ heart out for good measure.

The tension in the air for this entire game was thick and only got stronger as afternoon turned to night. There was the weirdest touchdown ever, the Jarrett Boykin fumble recovery and awkward run to the end zone. There was the eight point Chicago lead in the fourth, those harrowing Jordy Nelson fourth down conversions, that last play – the John Kuhn block, the defender’s momentary, fatal, freeze, and Cobb going on by. There was the decade that ball was in the air, and finally Cobb’s eventual catch. There was Rodgers’ celebration down the field after that, and the usually-forgotten last ditch drive by the Bears that actually moved dangerously close to the end zone.

Aside from the playoff against Baltimore in ‘65, last year’s finale was the only one of these division titles that not only came down to the last game on the schedule, but was also won in a head-to-head game with the only other team that had a chance to win the division. It’s the basic definition of do-or-die in a football sense, and it could happen again this season. We should probably start emotionally preparing now.