The steady beat: Cliff Christl talks about his career covering the Packers, his new role with the team, and all the work left to do

This story appears in the December 2014 issue of Packerland Pride magazine. Subscribe to the magazine here.

—

Today there is a word they’d use to describe the days and nights before Green Bay East and West High Schools met to play football in the 1900s, 1920s, the ‘30s, ‘50s. In those decades, all those years ago, Green Bay was geographically split by a river and divided by sides. Neighbors and archrivals. In those days the word they often used to describe what happened as the pre-kickoff hours ticked down is fighting. Today they would call them riots.

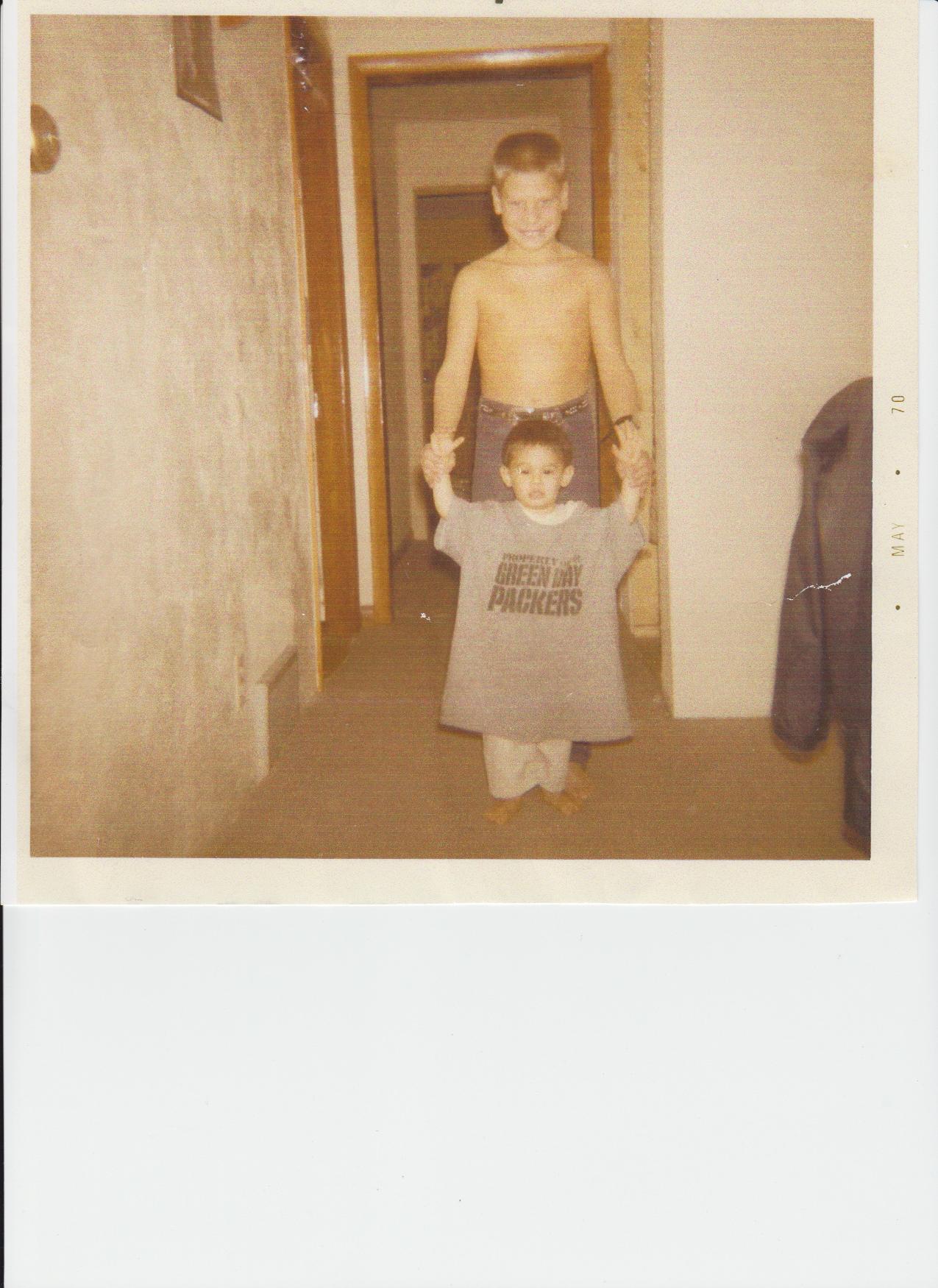

Cliff Christl grew up in Allouez and graduated from East High in 1965. He knew, as everyone living in Green Bay knew, that you stayed on your side of town. Even the riots – or fights – took place on bridges, eastsiders and westsiders still not willing to fully go to the dark side, instead meeting on no man’s land above the city’s shared river resource.

It was an accepted part of life in the Green Bay Christl grew up in. You didn’t go west if you were east, and a riot was a fight. Sports draw invisible yet present dividing lines across populations all the time. Green Bay’s natural split made the factions all the more secluded on their respective side, nestling snugly in their visceral hate of that other part of town.

In the early ‘20s the strangest thing happened amidst the fire and passion and violence. It started and wheezed and for a long time kept itself alive on the smallest rations possible. But on Sundays, as far as one topic was concerned, Green Bay found common ground, something more than a bridge to cross halfway for a brawl.

“I think the Packers were the one unifying force in town,” Christl says.

Christl would know, and not just because he’s now the team’s historian. It’s not because he is one of Wisconsin’s most prolific and popular sportswriters, his career spanning 36 years at four newspapers around the state, most notably the Green Bay Press-Gazette and Milwaukee Journal, or because he’s written or co-written numerous books on the Packers. Those stops on his career path, the seven Wisconsin Sportswriter of the Year awards, the two National Best Sports Story awards, the countless articles and stories, all the words he’s written on the Packers, are the results. The results of showing up and doing the work he not only believed he was supposed to do, but also probably the work he was, simply, supposed to do.

***

The first game Christl clearly remembers was the Packers’ last at City Stadium, against the San Francisco 49ers in 1956. When Christl says that’s the first game he has a really clear memory of, you believe him. After retiring from the Milwaukee Journal in 2007, Christl was already doing the job that became the actual position with the Packers he has today. He takes nuggets of Packers history and breaks them up, parsing out the details from the details and inconsistencies; leaving no stone unturned, as he says. While he enjoyed the retired life, spending more time with his wife, traveling, free from the pull of the deadline, Christl was spending most of his days researching Packers history anyway. His initial idea was to write the definitive history of the Packers, something he doesn’t believe yet exists. This makes sense, because if there were a way for this definitive history to get up and walk, it’d probably look like Christl.

Christl, for many already after his decades in the newspaper business, and many more now reading his history columns on the team’s website, is basically Packers history incarnate. After spending close to 15 years pouring through library microfilm – just him, the film, copies, and a notebook – he realized he could be doing this same thing for another 15 years before considering the pages and old papers scoured deeply enough to be ready for a book. A few discussions with the Packers later, and Christl decided it made the most sense to share the research. His work has always been about sharing information, Christl the consistent vehicle between the public and what was happening on the inside

That was a constant in Christl’s newspaper work. The reporting made the writing. Christl writes straightforward, directly. It comes from an analytical place, from wherever the reporting, the interviews, the information, took him. There’s a quote Christl remembers. He attributes it to Dan Jenkins, the great Sports Illustrated writer and author who now primarily covers golf. To paraphrase, it’s about informative writers, who you’re going to learn something from, and entertaining writers, who may or may not do that, and with or without substance. And there’s a smaller pool of writers who are both.

“I feel like I was an informative writer,” Christl says. “If they were looking to be entertained they probably went elsewhere.”

Getting the details chemistry-right, not just cooking-right, the reporting, developing of sources, those were always the base from where he started. But after spending the better part of three decades documenting the daily grind in front of his eyes, history finally snuck up and caught him.

“That is one of the things I have regrets about in my career. I have met some of the legends of the game, players who had played for the Packers in the 1920s, ‘30s, was introduced to people who were on the board in those early years,” Christl says, “and when you start out in the business all you’re interested in doing is doing what you have to do today to get your job done.

“You don’t care as much about history. But over time you realize how important that is, even in terms of how it can affect the future, and how important it is to learn from history … When I came up with some ideas to dig into the Packers’ early history – I wrote a story about how Curly Lambeau wasn’t really the first coach of the Packers (one of his National Best Sports Story winners) – and that required a lot of time and research. Once I started and got into that it really intrigued me. I think I sensed early on after I got into it, that this, there’s no story in sports that compares to this. And not only that but the history, that early history, is pretty muddled, and in fact the true story is better than the myth, which is a rarity.”

***

Some Christl history: He got into journalism, somewhat ironically now, when it hit him that his college years were nearing an end and he was going to need a job. As a junior at the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh, he started working at the campus radio station. Then he took a couple of journalism courses as a senior, then started to write for the student newspaper, also freelancing for the local paper on the side. He didn’t finish with a degree in journalism, but landed a job at a newspaper in Manitowoc.

He didn’t have the journalism school experience. Christl always liked following sports – football, baseball, basketball – though, and it made cosmic sense that the way he took them in growing up was by tracking rosters, watching games to rate and scout players, rather than rooting for a particular team. (Though he says he was as wrapped up in Vince Lombardi’s Packers teams as anyone, because of course.)

Christl spent a little over a year in Manitowoc, where he’d occasionally come up to Green Bay to cover Packers games, before joining the Press-Gazette. For nearly three years he covered high school sports and wrote sidebars on the Packers, gaining valuable on-the-job training.

Then, when Lee Remmel was hired as the Packers’ Public Relations Director, the Press-Gazette’s beat needed a new reporter. It was 1974. The Watergate scandal was fresh in everyone’s collective memory. The job of Packers beat reporter, which Christl says up until 1973 was basically a mutually beneficial relationship between the paper and team – the Press-Gazette has deeply-planted roots in the formation, early promotion, and survival of the Packers – was about to change. Christl, in another cosmic turn, had the perfect mindset for the shift.

“When I was given the beat in 1974 for the Press-Gazette I was given specific instructions,” Christl says. “That was during the Watergate era, and I was given specific instructions by my managing editor that I should cover the team the same way that writers in the big cities cover their teams. I was told, ‘I want you to be aggressive and cover the news.’”

Today a media pass is required to get past security and inside Lambeau Field. Media access periods are carved little chunks of time out of busy, already-long days for players and coaches. When Christl started on the beat he walked in the front door of the small offices on the north end of the stadium, went up the steps, knocked on a coach’s door, and walked in. He was still learning as he went, how to interview people and tackle stories. But he always had an attention to detail and a background of living room research that was starting to pay off.

“I was lucky because of how much interest I had as a kid in football,” Christl says. “For example, when I started out in ‘74 covering the team, I could name every player on every roster, so if I called up a general manager from one of the teams in the NFL and heard something about a trade rumor or somebody suggested there might be a trade in the works, I could rifle off specific names just like that, ask them is it this guy or this guy. So some of what I had done to prepare myself just as a young kid helped prepare me.”

***

National coverage, places like ESPN, hadn’t yet descended upon Green Bay in those days, so local competition fueled the chase for daily stories. Milwaukee papers weren’t yet sending up reporters more than a few times a week, so Christl primarily battled TV and radio sportscasters. Sometimes he’d have to wait 24 anxious hours for a story to run in the next day’s issue, hoping the TV and radio guys didn’t scoop it in the meantime. He says the Press-Gazette broke most major stories involving the Packers. The media competition in Green Bay – with up to four places: the Press-Gazette, Milwaukee papers, often one from Madison, and the Green Bay News-Chronicle – was rare for a city of any size. Still, most of today’s beats, especially the Packers, are saturated and varied in comparison. Christl is glad he worked in the era he did.

“If you worked and did your job you could break stories. Now there are so many people trying to break stories in so many different ways, I don’t know that anybody can even keep track of who the original source was on something,” Christl says. “It just all gets lost in the shuffle. So I think it was at least more rewarding back then.”

In October of 1986, after 10 years on the Packers beat and three as the Press-Gazette’s sports editor, Christl left for the Milwaukee Journal. The Journal wanted a writer that could pick their own stories on any sport in the state. It was what they wanted. But just as important was the type of writer they wanted.

“They wanted somebody to take a hard-nosed edge in their reporting, so it was too good of an opportunity to pass up,” Christl says.

About that edge. Christl’s voice as a writer has been commonly described as curmudgeonly, or cantankerous, or pick your own synonym for either of the two. Hard-nosed falls pretty closely in line with the persona Christl had on the beat and still has in general. You can feel that hint of old salty journalist in a conversation with him today. And yet that hint feels like it is there because he wants things right. Not for the sake of being surly, not distinctly for an image. Though he acknowledges the importance of editors and that everyone makes mistakes, he also doesn’t have much patience for errors in research. His place as the aging historian, the curmudgeon, are the results of all those years spent developing sources, using his instincts on the beat, and later the years of time spent with microfilm of old newspapers. If he sees an inaccuracy it, in a way, goes against all the work he’s put in. To say he takes it personally is probably going a bridge too far, but he does want the correct facts out there. Looking from his perspective it makes sense. After all, what’s the research for, if not that?

After joining the Packers in February, Christl has been asked how it felt to, in a sense, switch sides. People may have been worried he’d lose that edge. But that assumed persona was just another result of work. Read his articles on Packers.com and that same, direct voice hasn’t changed.

He isn’t or hasn’t been, thankfully, interested in throwing hot take after hot take against the wall to see what stuck or riled people up. When he’d get into a disagreement with the Packers on the beat – there were “a lot spats,” as he says – over a story he broke, it was based simply on the fact that he broke it.

“I just tried to be analytical and report the news. Tell the people what was going on inside the team,” Christl says. “I always felt like I had a good relationship with people out here. Always had great sources. I always felt like I treated people, anybody I dealt with out here, with respect. I was just doing my job, didn’t have an ax to grind, just going to work and doing what I was instructed to do.

“Obviously my approach changes here but as I told people, I didn’t feel at all conflicted because I was just doing what my bosses wanted me to do. That’s what I was hired to do, simple as that.”

***

After taking a buyout from the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel in ‘07, Christl settled into retirement. He never shook that love of microfilm deep dives, though, or the desire to share with people the history of the Packers. In November of 2011 he and his wife, Shirley, founded the Packers Heritage Trail, the walking tour guided by 22 plaques in downtown Green Bay that highlights significant places of interest intertwining team and city history, like Curly Lambeau’s office or the soon-to-be-reopening Hotel Northland.

All these years covering the Packers, the tedious research, and it still feels like Christl has just recently found his calling. There are still questions to answer. Even though, like the first meeting to organize the team, some are probably resigned to historical mystery.

“There are things I’d love to know that I’ll never know,” he says.

Listening to Christl go into detail about his searches for these old facts is enthralling for someone with an interest in this sort of thing. We get into the meeting.

“There was one sentence written about the initial meeting,” he says. “And I do not believe anyone knows anything more about that meeting than what was written in that one sentence, and that was it was held at the Press-Gazette on August 11, 1919. Didn’t say who was there, didn’t even say (Press-Gazette sports editor George) Calhoun and Lambeau.”

Technically speaking, Christl agrees when asked, we don’t even truly know if Calhoun and Lambeau were present at that meeting. Not for certain.

“There could have been two people there, there could have been 30. I suspect a smaller number, 2-5,” Christl says. “The reason I suspect that is because there was no notice of the meeting given in the Press-Gazette, so back in that day how would people have found out? That was very unusual of the Press-Gazette not to announce meetings about the organization of sports teams. And before the second meeting they did carry a story where they announced a second meeting was going to be held, and invited 40-some prospective players to show up. Prior to the first meeting there was absolutely nothing.

“That’s one of the problems with history being muddled. People find nuggets and they then draw conclusions from those little nuggets that might not be correct. You find a nugget, then you need to research the nugget before you determine how true or factual it is.”

Those old Packers creation stories captivate Christl, probably because they’re the hardest nuggets to dig up, to separate myth from reality. We agree that the sheer implausibility of the Packers even being here still to this day makes those origin tales all the more interesting, and important, to keep telling.

“They were basically on their deathbeds from the first day of practice, the very first practice, to the day they dedicated the stadium here,” Christl says. “They could never count on tomorrow coming, but it always came. It was just remarkable how history unfolded.”

The stories are great. They all build the unfathomable truth of this team and city, so long as you get the details right.

We continue talking about Calhoun and Lambeau. Before those meetings at the Press-Gazette was their famous chance encounter in a Green Bay bar. Or was it a street corner? We dive in. (Okay, Christl dives in; we listen.)

Christl nixes the once-held notion that they met at a bar called Shamus O’Brien’s, now The Standard & Company Bar on Main Street, because it wasn’t opened until the mid-‘30s. The near-universal belief, backed up by Calhoun’s own written histories and those of some of his peers at the Press-Gazette at the time, is that Lambeau and the sports editor who remembered Curly’s high school exploits at Green Bay East met on a downtown corner and got to talking.

In general this is the widely accepted intersecting moment that started the Packers. But in detail? Well, there are still answers out there that need finding. In an interview with Remmel before his death in 1963, Calhoun said he ran into Lambeau on his way back from the Baltimore Diary Lunch, a restaurant Christl says city directories put right next to the Vic Theater, recently Confetti’s Club, in Green Bay. About a block from the Press-Gazette’s old building.

“I was suspicious because why mention this 40 years later, and he’d written his own histories of the team and how things got started,” Christl says. It was the first time he’d ever heard Calhoun mention the Baltimore Diary Lunch. The detail triggered Christl’s honed red flag detector. Off he went.