Catching up with David Whitehurst: The former Packers quarterback built new life after football

This story appears in the January-February 2015 issue of Packerland Pride magazine. Subscribe to the magazine here.

—

The Green Bay Packers were turning it around in 1978. After finishing the 1977 season 4-10, Green Bay was off to a 6-2 start and hosting the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, which had only been a franchise for two seasons entering ‘78. And winners of two games in those first couple years. But that season the Bucs, at 4-4 entering their Week 9 game at Lambeau Field, were off to their strongest start yet.

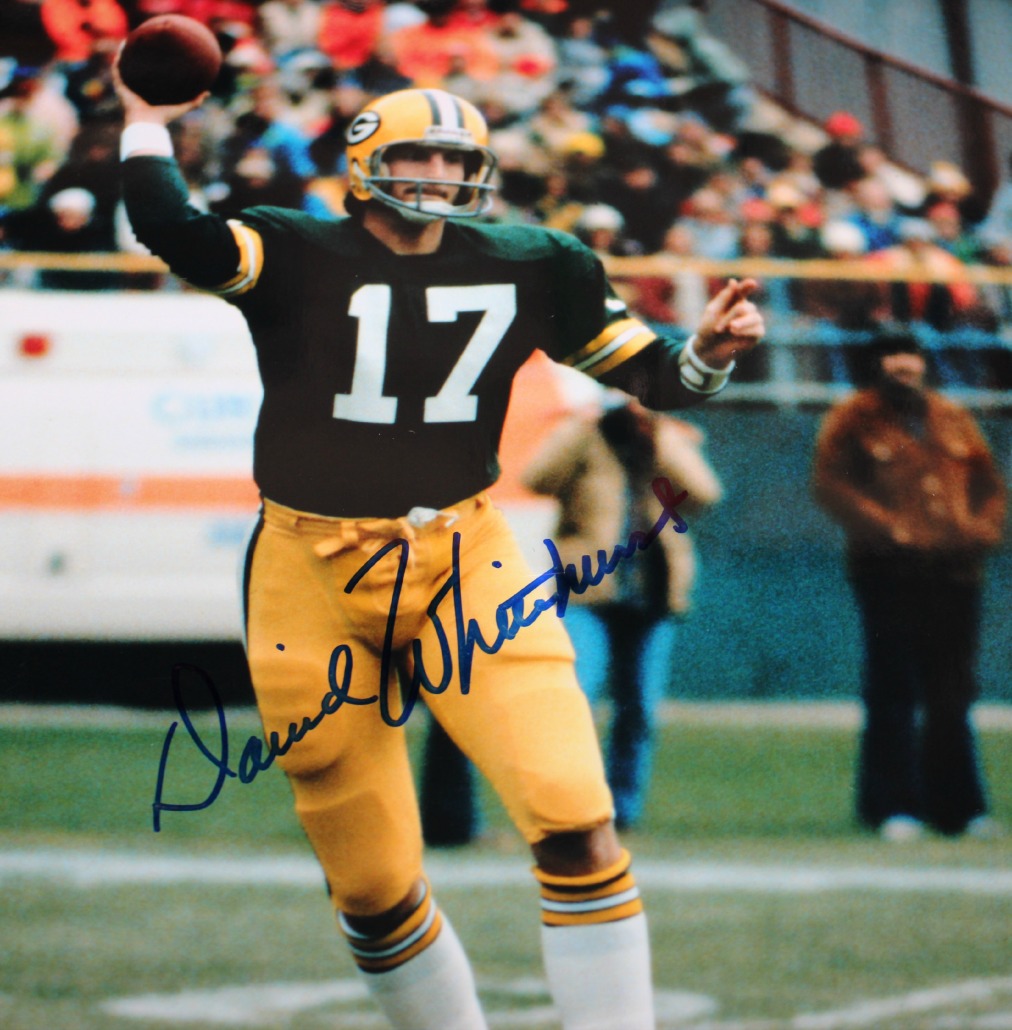

For Bart Starr, in his fourth season as head coach in Green Bay, it was also his best season to date on the sidelines. A year before the Packers finished 4-10, but won two of their last three games with rookie eighth round pick David Whitehurst, from Furman, starting the final five regular season contests at quarterback replacing an injured Lynn Dickey. After being thrown into the fire as a rookie in ‘77, Whitehurst went on to start the entire ‘78 season and first 13 games of ‘79 in Green Bay, learning under Starr, Dickey, and those around him. He played seven years in Green Bay, eventually playing spot duty behind a healthy Dickey again, before joining the Kansas City Chiefs as a reserve for a year, then retiring after the 1984 season.

With Green Bay trailing 7-6 and 1:25 left in the fourth, the ‘78 Packers were a play away from falling to Tampa Bay at home. From Tampa’s 47, though, Whitehurst connected with wideout Steve Odom on fourth-and-10 to advance inside the Buccaneers’ 30, setting up a game-winning 48-yard field goal by Chester Marcol four plays later.

The Packers were 7-2. In the following week’s issue, Sports Illustrated’s Dan Jenkins wrote a lengthy feature on the team, under Starr, potentially on the rise after the sun decidedly set on the Glory Years of the ‘60s.

In the feature, Jenkins wrote on the new cast of Packers, assembled largely by Starr’s strong draft classes:

If the Packers are indeed turned around, or if the Pack is almost back, it is because of all the new faces wearing the dark green and gold, players who have come primarily from the draft instead of via trades. They have a defense which has taken on one of the better nicknames — Gang-Green — and an offense that is built around that notable brokerage firm of Whitehurst & Middleton.

It turned out to be true, though maybe not to the extent it appeared to be going after the Tampa Bay win. Green Bay finished with only one more victory that year, but the 8-7-1 mark was the team’s first winning record since 1972 nevertheless. Whitehurst, as was the case for the team in general in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, had a balance of good times and bad on the field in Green Bay. But Whitehurst remembers his time as a Packer fondly because, for him and many other alumni, being a Packer turns out to only be partly about what happens on the field in the end.

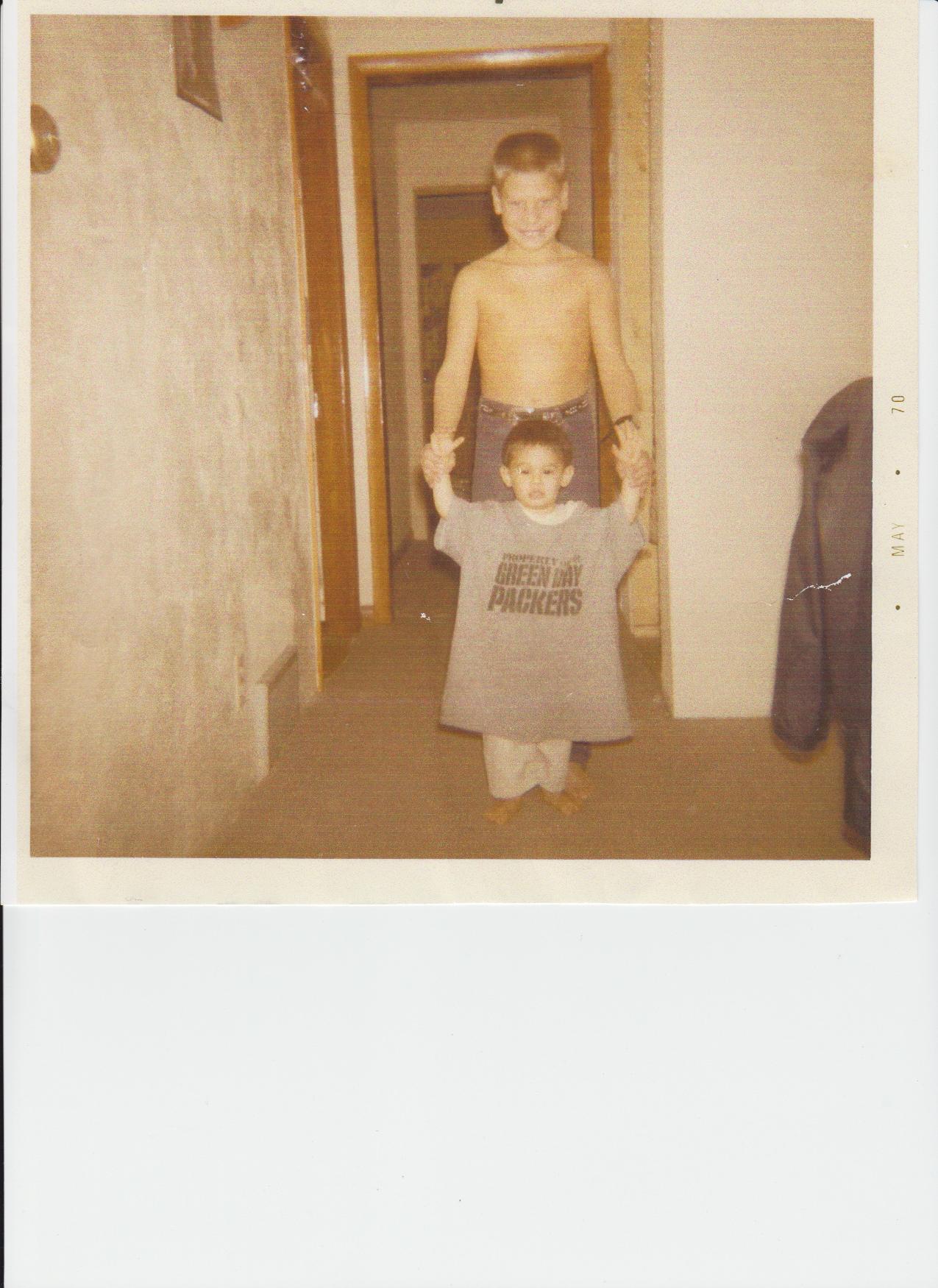

“What I would say is that at the time, even though I was a Packers fan growing up, I had no idea what it was like to be a Green Bay Packer,” Whitehurst says on the phone from Atlanta. “And I was so lucky and fortunate to have been drafted by the Green Bay Packers.”

Part of what that means comes from his teammates. Whitehurst says he knew they were close, but as time has gone on it continues to resonate, the unique bond and togetherness those teams had. As just a “green kid,” as Whitehurst says, his locker sat next to Dickey’s and later kicker Jan Stenerud’s. “Those are great memories, they taught me a lot,” Whitehurst says.

Whitehurst still keeps up with some of his old teammates. His son, Charlie, plays quarterback for the Tennessee Titans along with Chase Coffman, son of Packers Hall of Fame tight end and Whitehurst’s roommate for a few years in Green Bay, Paul Coffman. Coffman was also one of Whitehurst’s main passing targets during their playing days. On October 5, 2014 Charlie connected with Chase on back-to-back nine-yard completions in the third quarter of a game against the Browns, completing the rare occurrence of two fathers who played together getting to see their sons do the same thing they did many years ago.

It started with Starr though, who, being Whitehurst’s favorite player as a boy, went on the surreal path from being a player Whitehurst idolized to a day-in, day-out leader by example.

“We were young, 22 years old, and to have someone like Bart Starr to be a role model and someone we work with, and we saw how he operated every day, I was truly blessed to have people like that in my life,” Whitehurst says. “All I know is that he (Starr) is one of the finest humans alive. (Formers Packers quarterback, then later Packers assistant coach) Zeke Bratkowski used to describe him by saying, ‘If all the people in the world were in a big pile, Bart Starr would be sitting right on top.’ And I would agree with that.”

After a season on the sidelines in Kansas City, Whitehurst retired from the league with a plan for the future already in mind. He remembered working during the summers in college for his father, who worked in real estate and as a homebuilder. He remembered, during the NFL strike in 1982, looking forward to watching This Old House with Bob Vila every week. He knew what he wanted to do when football was over.

“My dad had two partners, and one of his partners was about 15 years younger than my father and 15 years older than me,” Whitehurst says, “so I approached him and said, ‘Look, I want to learn to build houses, would you teach me?’ So we built five houses together, and that’s how I got started. I had David Whitehurst Homes, and that’s what I’ve done ever since I got out of football.”

Whitehurst primarily oversees the business decisions, setting up schedules and doing payroll. Outside of homebuilding Whitehurst married his college sweetheart, Beth. Whitehurst says their first date was right around the time he got drafted by the Packers. He has spent most of his years raising his four children and coaching them in anything from baseball to football. Depending on the Titans schedule, he watches every Packers game he can. After coaching Charlie for fifth, sixth, seventh, and eighth grade, Whitehurst has been able to give valuable advice to his son following his father’s footsteps — “As a pro it was more of a what to expect next-type of thing,” he says — but primarily is just a parent, watching and rooting like any other.

“The overriding emotion is that you’re just pulling for him so hard,” Whitehurst says. “I don’t think they’ll ever know how hard you’re hoping it goes their way.”

When he has to get on the floor to inspect something in one of his homes Whitehurst says it’s a little harder to get up, but other than what goes along with getting older, he says he feels pretty good these days.

Though up and down record-wise, Whitehurst has always been thankful for the Green Bay faithful’s unwavering loyalty. Still very much following up Vince Lombardi’s championship teams wasn’t an easy task. Wins and excitement surrounding the team, like the attention they earned after that last-second Tampa Bay win, came and went. But on it or off, there were still great moments for every on-field misstep. Charlie was born in Green Bay, for example. Whitehurst enjoyed the small town atmosphere with Coffman and his teammates.

There were good games, too, of course. In 1979 Whitehurst started the first-ever Monday Night Football game at Lambeau Field. Facing the New England Patriots, 3-1 at the time, the Packers forced six turnovers and Whitehurst piloted the offense, throwing a touchdown in the second quarter to give Green Bay a lead they’d never relinquish in a 27-14 victory. Before that Packers Monday night games were played in Milwaukee.

“They had to upgrade the lighting at Lambeau so that it would be bright enough for TV cameras,” Whitehurst says.

For awhile, though, his football career was a difficult thing for Whitehurst to deal with. Asked if he thought it was ultimately beneficial to be thrown into live-action as a rookie — a rookie from a college that used a run-heavy offense, no less — Whitehurst chuckles briefly before answering.

“That’s funny, because it took me probably 10 years to reconcile how my career went and to feel good about it,” Whitehurst says. “We all want to be our best at what we do, and I wasn’t, and it took me a while to realize that, okay, I had some success, I had some failures, and it’s not a whole lot different than a lot of players that played in the league. But it took me awhile to be able to deal with it, have some closure with it, say okay, I’m good with it now, I’m moving forward.

“Time heals. The one thing you’ll hear, I think, as a common thread about football players is that the highs are high, but the lows are a lot lower. You dwell on the losses and it just eats you up. It’s kind of a condition: With the excellence that you’re striving for, when you’re not, when you didn’t win you didn’t do your job.

“And I don’t think the coaches did anything in addition to make you feel bad but I know where, the last four or five years of my career I didn’t play but maybe six or eight games, but the ones that we lost, that I didn’t even play in, I felt like were my fault for losing the game. It’s a conditioning of trying to be perfect and win those ballgames.”

It was a long time ago. Whitehurst grew up in Green Bay, learned, won some games, started a family, planned his life after football. He’s still active in Packers alumni get-togethers. And Whitehurst still, in his current life, remembers his old one in Green Bay with the clarity of time and an appreciation for what the experience still means to him all these years later.

“It was just the greatest experience of my life,” Whitehurst says. “I look at it with a different set of eyes now than I did when I was 22. I’m just so very fortunate to be a Green Bay Packer.”