You’ve never heard of the most unique receiver in Packers history: The (partial) story of Gus Rosenow, an original Packer and forgotten Green Bay wonder

This story appears in the March-April 2015 issue of Packerland Pride magazine. Subscribe to the magazine here.

—

Sunday, November 28, 1920. The Green Bay Packers were at the end of the schedule, facing the Lapham Athletic Club of Milwaukee. The 26-0 Packers victory that day wrapped up a 9-1-1 regular season, the Packers’ second as an independent team under captain Curly Lambeau’s guidance, organization, and stellar play.

One of Green Bay’s scores that day, against Lapham’s valiant but ultimately overmatched defense, came via a 30-yard touchdown pass. In those days this was quite a feat. Lambeau’s eye towards an aerial offensive attack was formed during his collegiate years playing for Notre Dame and coach Knute Rockne. But in 1920, the Packers were just beginning to start the forward-thinking revolution. Johnny “Blood” McNally was nearly a decade away from furthering Green Bay’s advanced use of passing. Don Hutson didn’t debut for the Packers until 1935. In their second season as a team, the Packers didn’t have someone to make the sort of plays as often as Hutson or McNally would later.

But on November 28, 1920, a lanky backfielder made a “flying catch of the oval” – as it was described in the next day’s issue of the Green Bay Press-Gazette – for a 30-yard touchdown.

He made it like Gus Rosenow made all his catches as a member of the original Packers teams: One-handed.

Packers history is scattered with one-handed grabs by receivers. Max McGee’s reaching-back, hungover snare and gallop for a touchdown in Super Bowl I. Randall Cobb’s one-handed over-the-shoulder catch in the end zone against the Bears last season on Sunday Night Football. Jordy Nelson pulling in some out-of-reach missile from Aaron Rodgers. There are thousands of examples, all in some way shocking as it happens. Grabs with one hand are always memorable in the moment. They all draw the same instant reaction: Was that one-handed? Did he actually catch that?

The degree of difficulty is high. We respond accordingly when it happens.

Gus Rosenow’s one-handed catches were different, though. Rosenow made them with the only hand he had.

–

Gus Rosenow, the Packers backfielder, is a mystery lost largely to time. He isn’t listed on the team’s all-time roster – the 2014 team media guide starts with the 1921 season to the present. He doesn’t show up in Pro Football Reference, the seemingly all-encompassing online database for the sport.

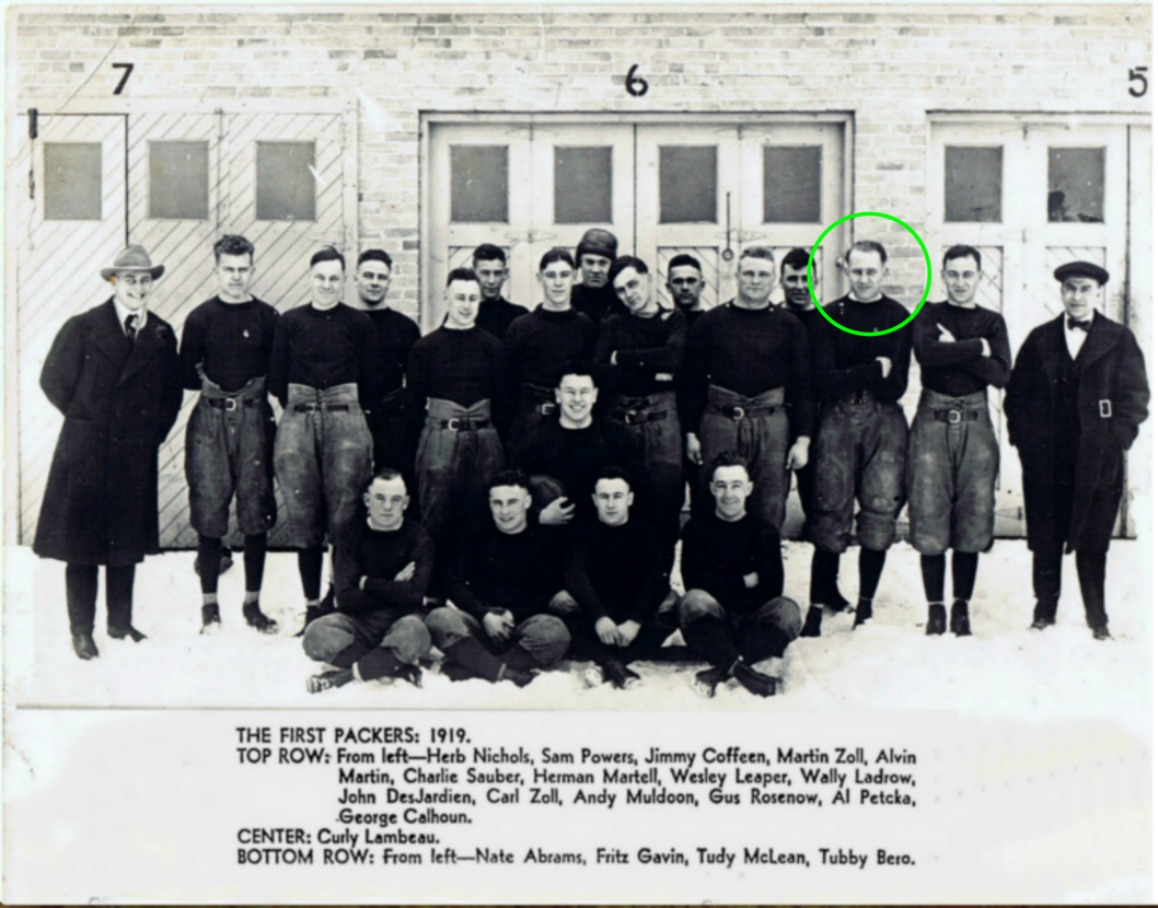

His name is included in some captions of team photos from 1919 and 1920, often just listed as “Rosenow.” Those days, this is how players were referred to in local papers. Surnames only – Lambeau, Rosenow, Abrams, Dwyer – no first names, only a first initial to distinguish Carl and Martin Zoll, brothers on those early Packers squads.

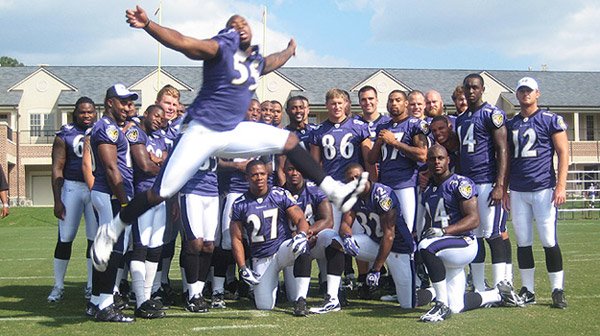

Anyway, being about six feet tall, Rosenow is always in the back row of these pictures. From every photo I could find, there is no photographic evidence that Rosenow had only one hand. In one, his torso is visible but his arms are crossed. Only one hand can be seen, though that’s hardly concrete proof that Rosenow was a one-handed pass-catcher.

More than that, the more I started going through contemporary books and online resources, the more I realized there was hardly any noteworthy mention of Rosenow on those original Packers teams. (Other than the fact that he was listed as a member of the team.) You’d be lucky to find a position for him through online research, which often turns up at least basic information on a former Packers player, much less an original.

That’s what was intriguing me: For the mythos attached to these teams – Lambeau, George Whitney Calhoun and the team creationism stories that read almost like folklore – it felt strange to have so little on one of those players. Especially one who not only played with one hand, but played really well, by most accounts, with one hand. It made me wonder: How big of an impact was Gus Rosenow on the original Packers teams? And did he really play with one hand? That seems like an interesting story in any age.

Then, I remembered part of what Cliff Christl, Packers team historian and longtime Wisconsin sportswriter, told me about the early, early Packers when we spoke in late 2014:

“The history, that early history, is pretty muddled,” he told me. “And in fact the true story is better than the myth, which is a rarity.”

If Gus Rosenow was lost in time, the only place to go was back into that history. To find some true accounts of those teams and games. Try to learn more about a guy who it seemed shouldn’t have gotten lost in the shuffle. Even if we are approaching 100 years since the 1919 team, shouldn’t a one-handed receiver get a closer look?

The best way to get the pulse of day-to-day goings-on from generations gone by is eye-crossing microfilm of old daily newspapers. So I went back to 1919. And the start of a local football team.

–

First, an admission. I had no idea who Gus Rosenow was before I meandered across an archived article online. It was from the Iron Ore newspaper, which at the time covered the Twin City football team of Ishpeming-Negaunee, Michigan. On October 19, 1919, the Packers went up to Ishpeming to face an undefeated Twin City team. The Iron Ore’s account says Green Bay’s speed and depth overwhelmed the home team in a 33-0 Packers win.

Then, in the second-to-last paragraph of the write-up, this (emphasis mine):

“Lambeau, the Green Bay captain, played a star game. He is a former Notre Dame fullback and displays the result of expert coaching. Rosenow, a one-armed player who entered the game in the last half, showed cleverness at dodging. He also did the kicking during the time he was in the game.”

At this point, to me, he was a one-armed player. This would, of course, add even more impressive weight to his contributions on the field. Also, the same amount of intrigue for me all these decades later. And as mentioned, one team picture shows him standing, torso visible, with what appear to be a pair of crossed arms. Was he one-handed or one-armed? Was this article out of its mind? Was it some weird, dated figure of speech? (For example: Teams were often described as “husky” in old newspaper stories, which I believe was a compliment.)

It wasn’t clear at all, but one thing was: This disappointed Iron Ore account of the Packers’ sixth game of 1919 – that one sentence spent on a guy called Rosenow – opened up the rabbit hole. So what follows is what I now know about Gus Rosenow, his life circa 1919-1921 in Green Bay and with the Packers, then his post-football life after. It is a rough, incomplete timeline of sorts, from information gathered online and in text, through correspondences, and in plenty of microfilm from the Green Bay Press-Gazette back in the day.

–

Gustav Adolph Rosenow – called “Rosie” with the Packers and later “G.A. Rosenow” – was born in 1892. He probably grew up in Menasha and definitely studied in the College of Letters and Science at the University of Wisconsin. Shortly after college he started as a teacher and coach at Green Bay West High School. Newspaper accounts call him a “high-class” basketball coach. After the 1919 Packers season Rosenow returned to the hardwood sidelines for West. By 1920 he’s called the school’s faculty athletic advisor.

Meanwhile, Lambeau and Calhoun were busy trying to put together a football team. An article from Wednesday, August 13, 1919 includes a partial list of candidates for the new squad. Rosenow is not mentioned. He also isn’t part of a longer roll call of 38 guys in the next day’s edition.

Rosenow was also a football coach at West. An August 30, 1919 brief in the Green Bay Press-Gazette says Rosenow was set to coach the West football team.

And in the same issue there’s a notice: The first Packers practice will occur next Wednesday night, September 3.

On September 5, a report from West’s first practice sits next to a write-up on the Packers’ second workout. The Packers, according to the Press-Gazette, were being coached by West head man Bill Ryan, and captained by Lambeau.

Then, in the Saturday, September 13 edition of the paper – a day before Green Bay’s first game against Menominee – “Rosenow” is listed under the “FB” position in the lineup. (Lineups were usually printed before and after games, occasionally but not always along with scoring summaries.) Just like that he was there.

We don’t really know how or what exactly happened. But, maybe, who: Somehow, Lambeau and Calhoun came calling. Because by September 23, when West announces its 1919 football schedule in the newspaper, only W.J. Ryan is named as coach.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that Rosenow was totally out as coach at West. But somewhere between August 30 – when he was set to be West’s head football coach – and September 23, something changed.

–

In a preview of the 1961 NFL Championship between the Packers and New York Giants, famed sportswriter Red Smith mentions the 1919 outfit. (By the ‘60s the Packers legend as a team of champions built from little more than snow and an idea was already firmly rooted in NFL lore.)

Rosenow is, Smith writes, “among the hometown mob that Curly Lambeau recruited for the Packers’ first season.” Smith continues with this aside between dashes, mid-sentence, writing, “Rosenow, the coach at West High, was a one-handed end and a remarkable pass receiver.”

Forty-two years later, Red Smith’s attention to detail offers a great bit of assurance. Still, before and after I came across Smith’s article, I was curious how an astonishing footnote like this was hardly getting any press attention at the time. When that turned up, I’d have my first real feeling of discovery.

To make matters stranger, a feature in the September 24, 1919 edition of the Press-Gazette spotlighted John Sullivan, a sophomore football player at Green Bay West. Sullivan had only one leg. In practice he hobbled on a crutch, got close enough to the tackling dummy, then dove. He hit as hard as anyone on the team, the dummy “bounds against the earth with a thump,” the article says, when Sullivan would collide with it. An interesting story by itself, to be sure.

And, of course, made weirder by the fact that one of his coaches – now a Packers player – also played with one less extremity. It shows where the Packers were on the public’s radar while they were starting out.

Specifics behind Rosenow joining are never mentioned in the local newspaper. But he was on the Packers’ roster. He scored a touchdown in their 53-0 victory over Menominee. He’s in the pregame lineup again for the next game against Marinette, a 61-0 win. And for the first time, on Thursday, September 25, he’s listed among the names of players who need to be in attendance for tomorrow’s practice.

Daily coverage of the team was picking up. Games were all painted as fights to the bitter end – a 54-0 win over New London was called a “hard-fought battle.” In October, the paper started running a series of features by Walter Camp explaining the role and duties of each position on the football field.

Rosenow scored a touchdown in the aforementioned win over Ishpeming-Negaunee. Two days after the Packers’ next game – an 85-0 decimating of the Oshkosh Professionals – on October 28, a day without any other Packers-related stories in the paper, Rosenow’s one-handed uniqueness got some ink.

In a regularly-appearing sports column called “Looking Em Over”, writer Val Schneider would run through various talking points in a bullet point sort of style. It was, oftentimes, something like a late night talk show host’s monologue, in written form.

In one of his spaces that day, Schneider writes:

“Many spectators who have witnessed the football games in which the Packers have participated marvel at the playing of Gustav Rosenow, half back. “Rosie,” as he is familiarly called has but one hand, but his does not seem to handicap him at all. He is able to spear forward passes with the best of pass receivers, is a good open field runner and line smasher.

“His greatest asset, however, one connected with his backfield duties, is giving interference. Rosenow is a past master in the art of blocking and spills the opposition with due regularity. When he goes for a man he always gets him.”

And there is probably the most detailed, lengthy portrait of Gus Rosenow of the Green Bay Packers. He’d get nods here and there in game recaps. He scored twice against Chicago on November 9. After a winter coaching basketball at West High, he returned to the Packers, injuring himself in the October 3, 1920 game against the Kaukauna American Legion.

The following week he is listed in the paper’s injury report on October 7: “The lanky backfielder’s knee got a bad twisting in last Sunday’s game.”

Rosenow played the following Sunday versus the Stambaugh Miners. The contest was played in terrible conditions, the Press-Gazette calling the pouring rain the “the worst gridiron day in the history of the game here.” Water rose up to player’s ankles, everyone so caked in mud it was difficult to tell the two sides apart. In this game, a 3-0 Packers win, Rosenow caught the only completion for either side: A 15-yard catch in the third quarter. He caught a 20-yard pass from Lambeau the next week against the Marinette Professionals and ran in a touchdown three plays later. Green Bay won 25-0. Rosenow made a “nifty” 30-yard grab on Beloit in a 7-0 Packers victory on October 31.

Rosenow’s name was peppered into write-ups. You never knew where it’d come up. Or if.

Rosenow was listed in the lineup for the November 7 contest against the Milwaukee All-Stars, and in the following week’s 14-3 loss to the Beloit Fairies.

(A quick word on Beloit: During these first two seasons the Fairies were arguably Green Bay’s fiercest rival. Beloit upset the 1919 Packers in the last game of the season on November 23. The 6-0 contest nearly caused riots due to dubious officiating – and no doubt, gambling money lost. The referee, allegedly using an outdated rulebook from 1918, according to the Janesville Daily Gazette, called an offsides penalty on Green Bay, wiping the tying touchdown off the board. A December rematch was set for $5,000, the Janesville Daily Gazette notes, but was later cancelled by Beloit’s manager due to unseasonably cold weather. In any event, Beloit served up both of Green Bay’s only losses in 1919 and 1920. There was bad blood here.)

Previewing the Packers next game against Menominee after the 14-3 Beloit loss, the Eau Claire Leader wrote about Green Bay leaving the defeat an injured, beaten up team. Lambeau was hurt. And, as the Leader puts it, “Rosenow, another back, was pretty much used up at Beloit.”

Rosenow wasn’t in the lineup against Menominee. Or the next, against Stambaugh, on November 25. He returned Sunday, November 28, 1920, where he made the “flying catch of the oval” for his 30-yard touchdown against the Lapham Athletic Club of Milwaukee.

The Packers won. And Rosenow’s career with the team was effectively done.

An exhibition game ended the 1921 season – the Packers’ first in the National Football League (then the American Professional Football Association). The contest was a 3-3 tie with the Racine Legion on December 4. The meeting, a de-facto state champions