Master statistician

Goska digs deep for Packers research

Jeff Ash

Special to Packerland Titletown USA

Say, you wouldn’t have any old Green Bay Packers game films down in the basement, would you?

Not just any game films, either. We’re talking film of the Packers in action against the 49ers in San Francisco from 1950, 1951, 1952 or 1953.

If so, would you let Eric Goska know?

Those films would help Goska, a free-lance researcher, get closer to his goal of having complete play-by-play for every Packers game from 1950 to the present.

Goska writes a weekly statistics-driven column for the Green Bay Press-Gazette during the Packers’ season. He also has written two Packers history books that are crammed full of statistical insight.

“Packers history always intrigued me,” says Goska, who grew up in Green Bay. However, the record books of the ‘70s and the ‘80s never had what he was looking for.

“Who had the most 100-yard rushing days, the most 100-yard receiving days. That’s how my research began,” he says.

So Goska started compiling those kinds of Packers statistics on his own.

“In the summer of ’86, I graduated from college and came back to Green Bay and started going through microfilm,” he says.

Goska was in his early 20s, then. Today, he’s 54, and he’s still at it, working from the home he shares with his wife and two daughters on Green Bay’s east side.

He’s filled two tall four-drawer file cabinets. He’s filled three shelves with binders of play-by-plays of Packers games.

There also are binders of game summaries, along with books and magazines.

It’s a labor of love for Goska, whose day job is managing the office at a Green Bay church. He majored in math at Northwestern University and earned a master’s degree in sports administration at Indiana University.

Goska is proudest of one discovery that rewrote the NFL and Packers record books.

For years, Packers great Don Hutson was said to have caught a pass in 95 consecutive games, an NFL record. But in 1991, Goska found a 50-year-old error.

Goska found that in the 45th game of that streak – on Sept. 21, 1941– Hutson didn’t have a reception in the Packers’ 24-7 victory over the Cleveland Rams at State Fair Park in Milwaukee.

Goska contacted the Elias Sports Bureau, the NFL’s official statisticians since 1961. Elias insisted Hutson had been hurt and didn’t play. NFL rules say a streak remains intact if a player misses a game because of injury. However, the official scoresheet showed Hutson as a substitute player in the game, in which he intercepted a pass and kicked two extra points, but didn’t catch a pass.

“We blew it,” Elias president Seymour Siwoff told the Washington Post after Goska’s find. “In no way do I want to exonerate us. It’s our mistake.”

That meant Hutson instead had two streaks, one of 44 games ending with the 1941 season opener and another of 50 games from the third game of 1941 to 1945.

Goska’s find also meant that James Lofton actually held the Packers record for almost a decade, catching a pass in 58 consecutive games from 1979 to 1983. It became news in 1992, when Sterling Sharpe was chasing what was believed to be Hutson’s record of 95 games.

(For the record, Sharpe broke Lofton’s mark with a 103-game streak from 1988 to 1994. Donald Driver holds the current record of 133 games from 2001 to 2010.)

“I had all this information and I needed an outlet for it,” Goska says. His first book, “Packer Legends in Facts,” was published in the fall of 1992, and updated in 1993 and 1995. His second book, “Green Bay Packers: A Measure of Greatness,” was published by Krause Publications of Iola in 2002 and updated a year later.

Goska is still trying to correct what he believes is another error in a Packers record.

“I’m convinced that the record of 294 consecutive passes without an interception by Bart Starr is off by one. I’m adamant it’s 293,” he says.

Goska points to a game against the Detroit Lions early in the streak, which covered parts of the 1964 and 1965 seasons and is still the second-longest in NFL history. Starr attempted a pass at the start of the second half of that game against the Lions. It was wiped out by a penalty, but was incorrectly counted as part of the streak, Goska contends.

How does Goska find these things? During an interview, he plays show-and-tell.

The first things he lays on the table are handwritten sheets with the play-by-play from the Packers’ 1942 season opener. He got them from the late Art Daley, who covered the Packers for the Press-Gazette for more than two decades.

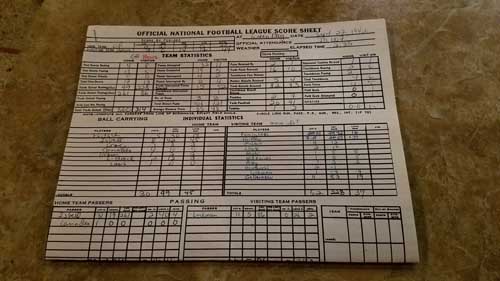

Art Daley’s play-by-play, the official NFL scoresheet and the next day’s Press-Gazette sports front, all for Packers vs. Bears on Sept. 27, 1942. The Press-Gazette obviously ran on the 28th.

“I wrote to Art in the early ‘80s,” Goska says. “That’s how my research began. I’d occasionally go to his house. He’d pull out these notebooks. He had them from 1942 to 1966, at least 25 of these notebooks.”

As he slowly worked his way through Daley’s notebooks, Goska had an idea.

“In the mid-‘90s, I thought it might make some sense to photocopy some of these. So offered Art $10 for every notebook I borrowed and copied. I spent $300 tops. I thought it was money well spent,” he says.

Art Daley’s notebooks were just one source for play-by-play from long-ago games. The Packers were another.

In the late ‘80s, as Goska worked on his first book, he was allowed access to the Packers’ archives.

“I sat next to Shirley Leonard for two or three weeks and hand-copied off scoresheets the Packers had,” Goska says. Leonard was the secretary for the Packers’ public relations staff.

Goska had been told by a colleague that the Packers had scoresheets dating to the 1940s, but didn’t know where they were.

“The Packers let me go in their basement in the old administration building. I discovered scoresheets from the late ’40s, from 1947 through the early ‘50s.”

Eric Goska’s color-coded play-by-play, notes and game summary for Packers vs. Bears on Sept. 27, 1942. They correspond to other materials in other photos.

In the summer of 1989, after Lee Remmel of the Packers’ public relations staff vouched for him, Goska spent three days doing research at the Elias Sports Bureau in New York.

“From the Lombardi era, I went backwards. I copied what the Packers had and Elias had the rest. I made a copy for myself and for the Packers as well, from 1947 back through 1933,” Goska says.

Getting the play-by-play is just the start. From there, Goska breaks it down further.

“I turn them into color-coded play-by-plays. Then I go through line by line to see whether the numbers match. That gets turned into my summary sheet,” he says.

“I keep track of some things they didn’t back in the day, like third-down efficiency.”

It takes Goska two to three hours to format his color-coded play-by-play summaries. He then transfers the information to an Excel spreadsheet.

“I have the Packers from 1954 to the present in spreadsheets. Every offensive play. Each year has its own spreadsheet. My goal is to do that for every opponent. That could take three or four years,” Goska says.

That’s where those old 49ers games come in.

“I’m trying to fill in the gaps for games I’m missing,” Goska says. “There are five games missing that could take my numbers all the way back to 1950. There are no play-by-plays on those games.”

Four of the five games are those 49ers games in San Francisco from the early ‘50s, all played in December at Kezar Stadium. The fifth game in Goska’s Holy Grail is the Packers against the New York Yanks at Yankee Stadium on Oct. 28, 1951.

“In the ‘30s and early ‘40s, when the Packers went out east, the Press-Gazette didn’t send a reporter, so those are sketchy games” for a statistician, Goska says. “In the ‘50s, the Press-Gazette didn’t send anyone out west at the end of the season,” thus no play-by-play for those games.

“I don’t have every game since 1933, but the vast majority I do have,” Goska says.

“The last two summers, I’ve been diving into the ‘20s. The Press-Gazette had play-by-plays, the Racine paper had them, the Portsmouth (Ohio) paper. I look at any paper I can to get details.”

Goska also joins other football researchers on a field trip to NFL Films in Mount Laurel, N.J., every other year. You know what he seeks.

“I’m looking for game film on games I don’t have a play-by-play for. I’m trying to create a play-by-play by watching the games,” he says. “We get there about 9 (a.m.), a group of us, we watch film, we break for lunch, then we go until 5 in the afternoon. We spend two days, then we head home.”

Goska has been a resource for Packers team historian Cliff Christl, who in 1986 hired him at the Press-Gazette as a part-time sportswriter covering high school games. He also has done some work for the Packers Hall of Fame website.

Goska has spent most of the last 25 years as a contributor to the Press-Gazette’s Packers coverage. He started with a small statistics-based feature in 1992 and expanded it to a column in 1994.

That, however, is the only place you’ll find Goska’s work.

His books, though highly regarded by fellow researchers, are out of print. He has no website. He’s not on social media. He has no cell phone.

“Just call me a Luddite,” he says with a smile.