The other George Halas

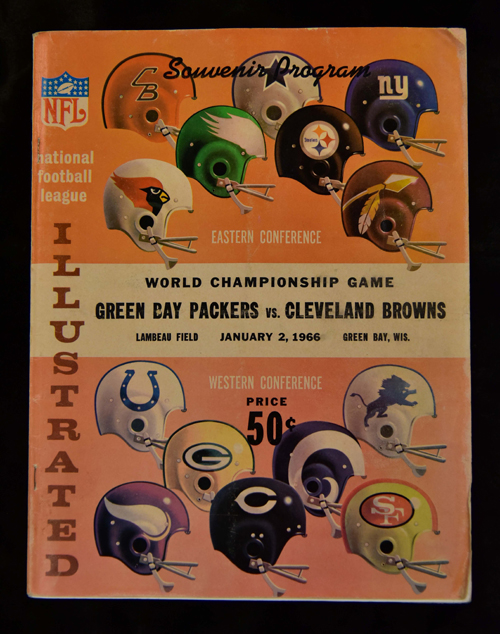

While Wally Cruice was scouting the Dallas Cowboys in preparation for the 1966 NFC Championship game, George J. Halas nephew to Pappa Bear Halas and a Chicago Bears scout filled the role for an AFC contest and impressed Vince Lombardi enough that the pair co-scouted the AFC Championship between the Kansas City Chiefs and Buffalo Bills. The Packers played the Chiefs in the second World Championship Game, a year after the contest in this program.

Papa Bear’s nephew played an unknown role for Packers

By Jeff Ash

Special to Packerland Titletown USA

Deep down, Art Daley knew George S. Halas, Sr. – Papa Bear – wasn’t a bad guy.

“I always kind of felt Halas was a friend of the Packers,” the former Green Bay Press-Gazette sports writer told David Haugh of the Chicago Tribune in 2011.

Indeed, the Chicago Bears’ founder and coach lobbied on Green Bay’s behalf in 1922, when the fledgling NFL wanted to expel the Packers for illegally using college players, and again in 1956, coming to Green Bay to speak in support of building a new City Stadium just before city residents voted on a $960,000 bond issue.

Asked for his opinion as the Packers looked for a new coach after the 1958 season, Halas told team president Dominic Olejniczak that he ought to hire a guy named Vince Lombardi.

“The Packers could not have had a better friend than George Halas,” Olejniczak said when the NFL legend died in 1983.

But the Packers had another good friend named George Halas. This is his story.

George J. Halas Sr. was a scout for his uncle, traveling on weekends to watch the Bears’ next opponent. He’d taken the job after his father died at the end of the 1959 season. Walter Halas was the older brother of the Bears’ owner and coach, and was the team’s chief scout for 17 years.

In December 1966, George J. Halas found himself at home in Chicago with nothing to do on the last weekend of the pro football season. The Bears weren’t in the playoffs, thus there was no next opponent to watch. So he picked up the phone and called up to Green Bay.

Halas told Len Wagner of the Green Bay Press-Gazette that the conversation went something like this:

“Tom, you need help,” Halas told Tom Miller, the assistant to the Packers’ general manager.

“We do?” asked Miller, who was Lombardi’s right-hand man.

“Sure, you do,” Halas said. “You need somebody to scout that other league for you on Sunday. You’re going to have

Wally Cruice scouting Dallas, Sunday, aren’t you? Then you don’t have anybody to scout the American League.”

That was true. On the Sunday before Christmas in 1966, Packers scout Wally Cruice was at Yankee Stadium in New York, watching the Giants’ season finale against the Eastern Conference champion Dallas Cowboys, whom Green Bay would face in the NFL championship game on New Year’s Day.

Cruice was a staff of one. On this particular weekend, there was no one to scout the rival AFL, whose champion the Packers would play if they beat the Cowboys in Dallas and advanced to the first Super Bowl.

So the Packers hired George J. Halas of the Chicago Bears as a scout.

On Sat., Dec. 17, Halas flew to New York to watch the Boston Patriots against the New York Jets at Shea Stadium. The Patriots had led the AFL’s East Division going into the game, but were upset by the Jets 38-28 and finished second behind the Buffalo Bills.

That trip gone for naught, Halas got back on a plane and flew cross-country to San Diego. The next day, on Sun., Dec. 18, he watched the West Division champion Kansas City Chiefs defeat the Chargers 27-17 at Balboa Stadium.

Halas sent the Packers his scouting report on the Chiefs. The Packers apparently liked what they saw. They hired Halas for another week, sending him with Cruice to the AFL championship game at Buffalo’s War Memorial Stadium on New Year’s Day, 1967.

As that game started, Halas kept his eye on the Chiefs. Cruice focused on the Bills. But when the game became a blowout in the fourth quarter, both men turned their full attention to the Chiefs, who won 31-7.

The 1919 Packers. Curly Lambeau, alone in the second row, had a long-standing love-hate relationship with George S. Papa Bear Halas. This famous photo originally ran in the Green Bay Press Gazette with the following caption: This is the Packer squad that started Green Bay rolling on its way to football fame in 1919. The members were left to right: top rowHerb Nichols, Sam Powers, Jim Coffeen, Martin Zoll, Alvin Martin, Abe Sauber, Herman Martell, Wes Leaper, Wally Ladrow, John Des Jardin (sic), Carl Zoll, Andy Muldoon, Gus Rosenow, Al Petcka, G. W. Calhoun; centerCoach Curly Lambeau; bottom rowNate Abrams, deceased, Fritz Gavin, Tudy McLean and H.J. (Tubby) Bero. The first Packers defeated Menominee, 53-0; Marinette, 61-0; New London, 54-0; Sheboygan, 87-0; Racine, 76-6; Ishpeming, 33-0; Oshkosh, 85-0; Milwaukee A. C., 53-13; Chicago A. C., 46-6; and Stambaugh, 17-0, but lost their last game to Beloit 6-0.

Early the next week, George J. Halas traveled to Green Bay and went to the Packers’ offices at Lambeau Field. He hand-delivered his scouting report just as Lombardi and his staff were watching film of the Chiefs’ defense against the Chargers’ offense.

Lombardi immediately put Halas on the spot. Halas told Wagner that it went something like this:

“Where are the deep backs?” Lombardi demanded.

“They’re deep,” Halas said.

“How deep?” Lombardi pressed Halas. “They don’t even show on the films. Don’t they come up and help on the short pass?”

No, Halas told Lombardi, the Chiefs’ defensive backs don’t come up and help on short passes.

As one of the scouts, Halas helped craft the Packers’ game plan for the first Super Bowl. He took that tidbit about coverage on short passes and suggested that the Packers send fullback Jim Taylor into the line on a fake and throw to the tight end or the split end cutting short over the middle.

That’s exactly what the Packers did on their way to a 35-10 victory over the Chiefs in the first Super Bowl.

Scouting was just a part-time gig for George J. Halas. He was moonlighting.

During the week, the 42-year-old Halas worked for General Electric. He was a salesman for GE’s Wiring Services Department in the Midwest.

One of GE’s products was a soil heating system for athletic fields.

At the time, only Falcon Stadium at the Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colo., and Busch Stadium in St. Louis had such systems, and the Busch Stadium system had never been turned on.

Halas had just sold one to the Packers, too. They became the first pro football team with the so-called “electric blanket” heating system under the playing surface.

At Lambeau Field, electric cables were laid about a foot apart, covered by six inches of top soil. Below the top soil and electric cables were six inches of pea gravel and drain tiles. The heat simultaneously dried the soil and made it more porous, making it easier for water or melted snow to soak down to the gravel and drain tile. The system was turned on either in certain weather conditions or by a thermostat set to a specific temperature.

“Under normal snow or rain conditions, the grass and soil will be the same as it is in the middle of August,” Halas said in Green Bay in February 1967, just a month after that first Super Bowl.

“If a heavy snow storm or rain storm is expected, the field should be covered with a tarp. But when the tarp is removed, the turf will be dry and solid. With this system, you can grow beautiful green grass all winter if you want to.”

When the tarp was removed before the NFL championship game on New Year’s Eve 1967, the Lambeau Field turf was indeed solid, but not solid as Halas had suggested. It was frozen solid.

The system Halas sold to the Packers had malfunctioned in the subzero cold, leaving moisture on the field while it was covered by the tarp. The moisture froze, creating conditions more like an ice rink than a football field.

That, of course, was the Ice Bowl.

George J. Halas Sr. had long, distinguished careers as a sales executive and in the military, serving in the Army, National Guard and Army Reserves. He scouted for the Bears until the 1970s. He died in 2000 at the age of 75.

The Packers currently have a scouting staff of 17 in what they call their player personnel department, 18 including general manager Ted Thompson, along with several that provide technological services.

Of course the coaching staff now has 23 members, including four in strength and conditioning, not counting five serving as athletic trainers.