Forging a relationship – Green Bay and the Packers

By Jeff Ash – Special to Packerland Titletown USA –

Bookshelves dedicated to the Green Bay Packers grow every year.

New books come along, telling another story, another chapter, snapped up by the faithful. The Packers’ legend grows every year.

Many Packers books, however, focus almost solely on what happens on the football field. But the Packers have never existed in a vacuum.

The Vince Lombardi era took place with the Vietnam War – and the war at home over the war – as a backdrop. That kind of context and perspective rarely appears in books about the Packers’ Glory Years, save for occasional mentions of players serving military duty during the long offseason. More often told is how Lombardi’s Packers handled race relations during the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

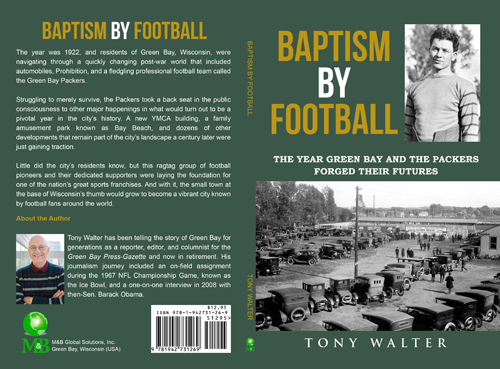

“Baptism by Football: The Year Green Bay and the Packers Forged Their Futures,” a new book by Madison author Tony Walter, tells the story of the 1922 Packers. He surrounds it with the story of Green Bay in 1922. It was a time when a small town and a football team grew up together.

The 1922 Green Bay Packers. Top row, from left, Lynn Howard, Jug Earp (misspelled in picture), Whitey Wooden, Dave Hayes. Middle row, from left, Curly Lambeau, Cub Buck, Lyle Wheeler, Moose Gardner, Charlie Mathys. Bottom row, from left, Walter Nieman, Dewey Lyle, Stan Mills, Jab Murray.

What should today’s Packers fans take away from a book that tells both stories?

“I think it’s helpful to understand the personality of the community at a time when the Packers were just trying to get a foothold,” Walter says.

It’s also a practical consideration. Walter’s primary source for the book was the Green Bay Press-Gazette. There was much more written about Green Bay than about the Packers in the newspaper in 1922. Walter’s book reflects this.

Green Bay in 1922 was a town trying to get a foothold in the 20th century. It had 16 cigar makers, 12 automobile dealerships, nine billiard halls, six electric streetcar lines, five blacksmith shops, four telegraph companies and one midwife.

Prohibition was the law of the land in 1922, but Green Bay was a wide-open town where beer and liquor still flowed, a place where law enforcement winked at gambling and prostitution at roadhouses and dance halls just outside the city limits.

Salesmen for the Green Bay Motor Car Co. pose for this photograph from the early 1920s. The dealership was at 316-318 N. Jefferson St. in downtown Green Bay. In 1922, Green Bay had 12 automobile dealerships but still five blacksmith shops.

Yet Green Bay had its eyes on the future, envisioning a more prosperous community. Among major construction projects announced in 1922: the high-rise Northland Hotel, a new YMCA and a new Knights of Columbus clubhouse that rivaled the YMCA, all downtown, plus a new East High School just 10 blocks away. Highway 15, a cement highway that ran from the Illinois border through Green Bay to Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, opened in August 1922.

You know it today as Highway 41.

Looking back to 1922 “also helps us to fully grasp how unique the franchise is to be able to survive when most city teams could not,” Walter says of the Packers.

As 1922 began, Green Bay was on the verge of losing its pro football team, having been caught up in a scandal over the use of college players. The Packers had used three Notre Dame players during a game against Milwaukee in Racine on Dec. 4, 1921.

John and Emmett Clair, who had held the Green Bay franchise in the American Professional Football Association since the previous August, surrendered it to the league in late January 1922. The league’s directors voted unanimously to drop the Packers.

That, Walter writes, left the Packers “on the outside of pro football and looking in.”

That’s where the story begins. Yes, the Packers were founded as a town team in 1919. Yes, they became a professional team in 1921. But it was in 1922 that Green Bay started building the foundation for the team that thrives today.

When American Professional Football Association owners reconvened in Cleveland in June 1922, Green Bay was one of eight cities wanting into the league. Of the eight, only Milwaukee was a big city. Among the others: New Haven, Conn.; Duluth, Minn.; Sioux City, Iowa; and Youngstown, Ohio.

Curly Lambeau, who in 1919 had co-founded the Packers, attended the meeting. He paid $250 to file an application for a franchise. After Lambeau promised that the Packers had new leadership and wouldn’t use college players, Green Bay was admitted to the league. There were four new teams – the others were Toledo, Ohio, along with Milwaukee and Racine – in a league that had a new name.

The Packers were members of the National Football League.

After playing an exhibition game against a club team in Duluth, the Packers opened the 1922 season at Rock Island, Ill., on Oct. 1. Three of the Packers’ first four league games were on the road, but Green Bay still followed its team on game day.

“I was intrigued by the fact that so many people would gather at the Elks Club, inside and outside, to get updates and play-by-play of road games sent by telegraph,” Walter says.

As October ended, a home game against Rock Island was not a proud moment for Green Bay. During the scoreless tie at Hagemeister Park on Oct. 29, Packers fans taunted Duke Slater, an African-American tackle for the Independents. In 1922, Walter writes, “the only people of color in Green Bay were transients or Oneida Indians who had left the nearby reservation.”

The Packers were 0-3-2 as November 1922 arrived. They improved on the field, going 3-0-1 in November, but poor attendance and bad weather caused financial trouble.

The Packers tried to make some money by raising ticket prices and scheduling a Thanksgiving Day exhibition game, but they struggled to find an opponent. The Chicago Bears said no. The Milwaukee Badgers said yes, but only if the game was played in Milwaukee. No deal. Finally, the Duluth Kelleys agreed to a return game, which was played on a muddy field before a tiny crowd.

That a pro team played a club team during the season is evidence that the NFL of 1922 still wasn’t far removed from its town-team beginnings.

The Packers hoped to schedule another exhibition game a week after they ended the NFL season on Dec. 3. But they couldn’t find an opponent within their means who wanted to play in Green Bay on Dec. 10. The Canton Bulldogs and Dayton Triangles wanted too much money. The Badgers again offered to play in Milwaukee, but wouldn’t give the Packers any financial guarantee.

The 1922 Packers finished with a 4-3-3 record, tied with Dayton for seventh place in the 18-team NFL.

Nine days after the season ended, Green Bay came to the Packers’ financial rescue. On Tuesday, Dec. 12, a group of 42 community leaders organized the Green Bay Football Club and agreed to sell 1,000 shares of stock at $10 a share.

“More than any other day in its history, December 12, 1922, saw the true baptism of the Green Bay Packers,” Walter writes. “And, it could be argued, the baptism of the city.”

Walter initially planned to write about the Packers’ first 10 seasons, from 1919 to 1929, but narrowed his focus to 1922 for his first book. Walter, who in 2012 retired from the Green Bay Press-Gazette after a 37-year career as a reporter, columnist and editor, plans to write more Packers history.

“I’m looking at the period from 1929 to 1933 when the Packers started winning championships, the city had to deal with the Great Depression and a fan sued the Packers after falling out of the bleachers,” he says.

“Baptism by Football: The Year Green Bay and the Packers Forged Their Futures” sells for $12.95. It is available from the Packers Pro Shop, at some Wisconsin bookstores and from Amazon. It also is available for Kindle ebook readers. It is published by M&B Global Solutions of Green Bay.