The quarterbacks

This story appears in the August 2014 issue of Packerland Pride magazine. Subscribe to the magazine here.

—

On the occasion of some list or another ranking Green Bay’s current quarterback outside a briefly topical top 10 list I’m sure we should take seriously, quarterbacks came to mind. More specifically, how ranking and putting them up against one another doesn’t really work. In some ways, sure, it’s simple. In touchdowns and interceptions and Count The Rings!, yes, it is easy, and it can work in an argument. But it’s also still a little simple.

People are all different. And players, who are almost all people per our research, are also all different. Take two of the quarterbacks who have exhausted the most words and thoughts of any: Tom Brady and Peyton Manning. You can rank them 1 or 2 or 2 or 1, but that’s boring, and basic, and what does it really say, anyway? Instead, it’s more interesting to look at what makes them the quarterbacks they’ve been for so long. So, in this example: Brady is adaptable to his surroundings, which have changed a lot over his career. His game shifts and changes with the players around him, all the while he remains the constant weight in the middle of the tradewinds, the guy keeping the boat sailing forward despite losing crewmembers due to things like the salary cap and sharks.

Manning on the other hand makes his surroundings adapt to him, everyone on the offense a cog in the machine that is his mind, all pieces on the Risk board of attempted football domination. Each of these guys, and everyone else, has attributes, ways of thinking through situations, have been presented with unique scenarios and reacted individually to them. And all of these variables make up any player’s status and worth on their own team and on a league-wide scale.

Comparing and contrasting is different than making a list and calling it definitive, and to me, only one of those makes enough worthwhile sense to spend time thinking about.

But anyway, I was also thinking about quarterbacks because the Packers’ current guy is right around some mid-point in his career, entering year 10, coming off a season where we witnessed his importance by watching him and not, after another offseason of changes and additions. It just feels like a good time, before the regular season starts, to think about and remember some of Green Bay’s memorable quarterbacks, of which they’ve had a few.

––

Arnie Herber was That Guy on the 1930s professional football scene. Here was everyone else, running all the time, multiple dudes getting carries each game, defenses gearing themselves towards stopping runs and sweeps, and then Herber shows up as a 20-year-old rookie in 1930 and throws three touchdown passes. In the first game of the 1930 regular season he uncorked a 50-yard bomb to Lavvie Dilweg, a score which helped give the Packers a 14-0 win over the Chicago Cardinals. A 50-yard bomb then was probably like watching a bubble screen to A.J. Hawk go for a 97-yard touchdown now.

A graduate of Green Bay West High School, Herber changed the game, literally, from that point on. In 1932 he led the league with 639 passing yards and 9 touchdown tosses. He’d lead the league in those categories two other times, in ‘34 and ‘36. He was a member of four world championship teams.

He was a longshot. After a decorated high school career Herber went unnoticed, leaving for Regis College (now University) in Denver to continue playing. Herber was a handyman with the Packers when Curly Lambeau let him try out for the team. Times were different then, but imagine Mike McCarthy catching a repairman throw a roll of duct tape to his partner, then giving the repairman a shot to try out for the Packers.

But Herber got this chance, and proceeded to, well, just throw the ball around everywhere. Don Hutson joined the team in 1935 and the first real quarterback-receiver duo in pro football was formed. Their first lightning bolt cracked in the second game of the ‘35 season; Herber hit Hutson for an 83-yard touchdown pass, on the second play of the game, in what would be the winning score against the Chicago Bears. The ball was said to have traveled over 60 yards in the air before getting to Hutson.

Herber was a shock to football’s system, the unexpected rush of change. Because of it, his and Hutson’s careers were memorable firsts. Herber was a longshot the whole way through, refining a position that really wasn’t one yet, not through dinks and dunks, but big shots that’d either work or not.

––

America was doing a lot of changing in the 1960s. But when Vince Lombardi took a chance on his earnest backup, Bart Starr, willing to learn and listen and develop in 1959, the Packers’ starting quarterback very often didn’t, and, like it was meant to be, there Starr was, the on-field face of the franchise’s greatest generation, one of the symbols personifying that era in Green Bay.

It doesn’t seem like it could be anyone else now other than Starr, right? How in the world do you explain he and Lombardi managing to find each other at these perfect times in their careers, other than fate? When Lombardi finally got his chance to construct the house his way, when Starr was plugging away in the film room, trying to tweak his mechanics just so. Both ready to build something of their own. They lost one playoff game, their first, together, out of 10. Starr never completed less than 54 percent of his throws for a decade, led the league in lowest interception percentage three times, was also the highest-rated quarterback in those three seasons.

Starr was the perfect complement to Lombardi’s thorny perfectionism not because he was perfect, but because he was always consciously, actively trying to inch towards that – careful yet deadly in his decisions – because he accepted perfect as an abstract standard of Lombardi’s but not a summit he’d ever reach. Both men understood that was the trick of it.

––

One of the things you could say about the Packers from the early-to mid-1980s was that they were, in a way, consistent. They finished 8-8 in four of those six years. (Going 5-10-1 in 1980 and 5-3-1 in strike-shortened 1982.) Oh, there were changes, too: they’d transfer from the tenure of Bart Starr as head coach to Forrest Gregg between ‘83-‘84; they weren’t as drudgingly subpar as they were in the 1970s and later ‘80s, before 1989.

In all, these six years were strangely mediocre times in Green Bay. Mediocre because 8-8 in four out of six seasons is simply that, yet strange because inside the bland, off-white exterior seen going by record alone, fireworks were going off, and Lynn Dickey was lighting them.

Dickey came in a trade from the Oilers in the late ‘70s. He led the Packers in passing for two seasons, was supplanted by David Whitehurst for another two before taking over long-term until his retirement after the 1985 season. Flanked by tight end Paul Coffman and receivers James Lofton and John Jefferson, Dickey slung the ball with, and this is with the value of hindsight, mind you, the carefree “let’s see what happens” mindset of a gunner during a contract year on a middling NBA team in the Eastern Conference. He was getting shots up and they were going in. Records he held in Green Bay include, among others: most passing yards in a season; in a single game; and highest average yards-per-gain in a season (9.21 in ‘83). He still holds the team record for highest completion percentage in a game (min. 20 throws) when he connected on 19 of 21 (90.48 percent) against the Saints in ‘81.

He is usually best remembered for the wild 48-47 win over Joe Theismann and defending champion Washington in ‘83, the highest-scoring game in Monday Night Football history, one part of an ‘83 campaign where he led the league in passing yards (4,458), touchdowns (32), and interceptions (29) because, hey, sometimes you’re gonna miss when taking so many shots, too.

That game and that season are often how Dickey is remembered, what he’s asked about most. I think it makes sense, not just because it was his statistically best season, but because the Packers finished, guess where, at 8-8. Enough of those run together and they could become forgettable, with the Packers’ history and present as bookends, pretty quick. But Dickey’s career in Green Bay helps us remember what those seasons were: consistent, in a way, not great, and yet, they found a way to stand out.

––

Take a bunch of steps back until you’re able to see the entire timeline of the Green Bay Packers and, sure, a career that featured only one full season at starting quarterback, the others split or thrown off course by injury, isn’t much more than a drop in a cup of coffee.

The impact that Don Majkowski has, the fan favorite the Majik Man still is, though, speaks to a player who left something behind here. Doing so in that compressed area of time only makes his legacy more impressive. That legacy is largely built around 1989, of course, the year they were known as the “Cardiac Pack.” That year they won four games by one point, Majkowski directed seven game-winning drives, and led five fourth quarter comebacks. Lifespans were shortened that season. Would anyone trade back the years?

These are the kind of games people don’t forget, in other words, especially the famous “Instant Replay” game when Majik rolled all the way, literally all the way, to the right before firing a cross-body touchdown to his favorite target, Sterling Sharpe, to beat the Bears after the play was first disallowed and then overturned. He led the NFL in passing yards (4,318), completions (353) and attempts (599) that year. The Packers went 10-6. Their first winning season since ‘82.

It is in this season leading the Cardiac Pack that Majkowski made his legacy. It is almost like he knew something that year. His young career hampered by injuries, spent rushed, almost always coming down to the last minute, Majkowski was out there cramming moments into Packers lore. It is almost like he knew he was short on time. Almost like he knew what was about to happen when he left a Week 3 game against the Bengals with an ankle injury on Sept. 20, 1992.

––

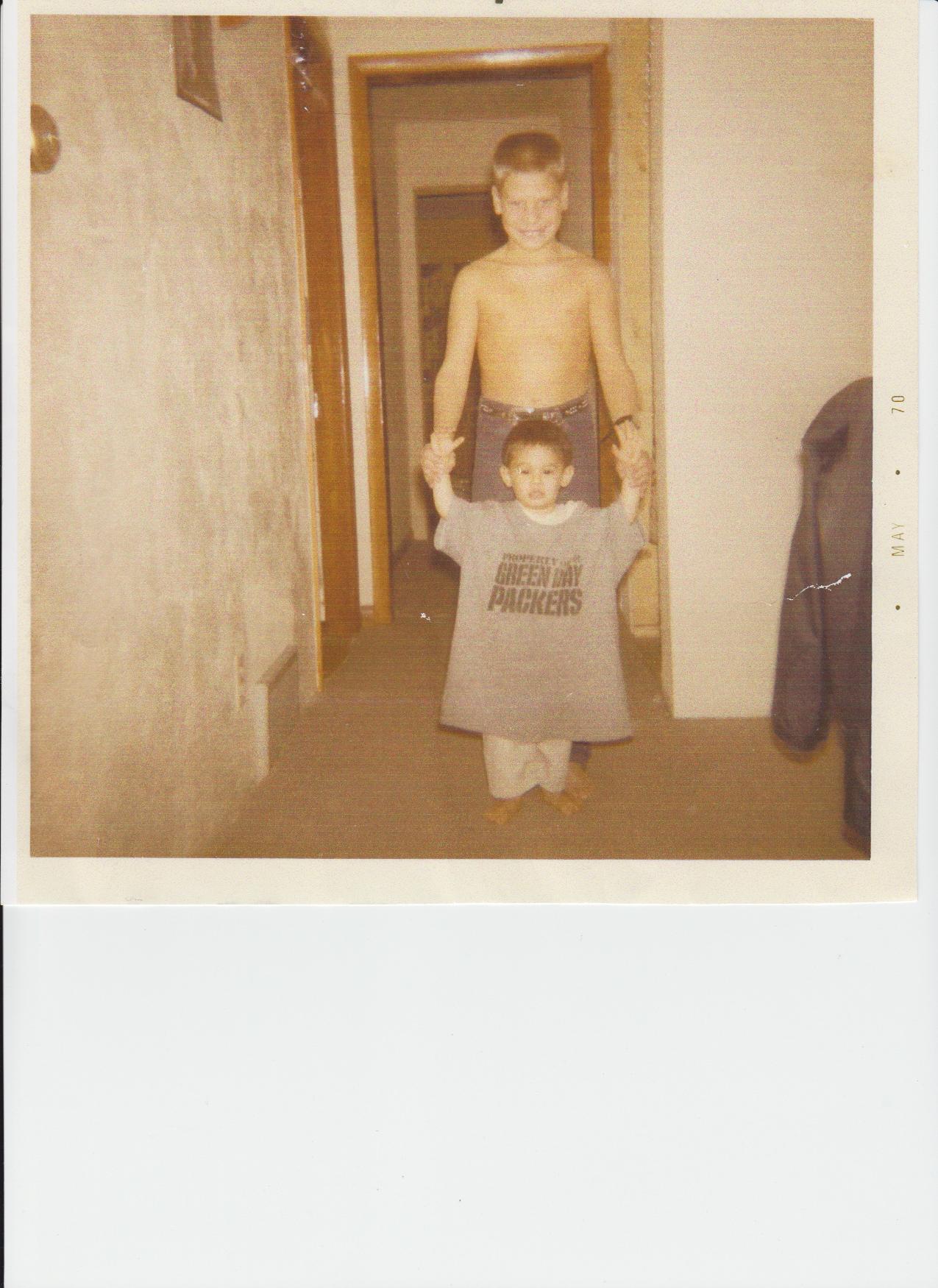

It is so strange already to think of Brett Favre as living in the same neighborhood with the sort of past I’ve always seen these other quarterbacks in. To have the guy who was there playing quarterback while I was absorbing my first Packers games as a tiny human, to growing up knowing only one guy and one style, then to grow out of that same guy and his style, going there to a place of disdain and back, now, to a better place again thanks to time. It all still feels so weird, doesn’t it?

Personally, I don’t think there will be a more important player for which it is absolutely vital to remember everything, the heart-aching highs, heartbreaking lows, the transcendence of one person in one city, the transcendent plays frozen in time, the Vikings and the Jets and the break-up, everything, good and bad, all of it.

As more years go by the feeling of all that embodied Favre, raw to the touch for so long in all directions, now numbs, white noise humming in the background. I just don’t think about it a lot anymore. But when I do, I’ve found that remembering Favre can’t be a passing glance down Memory Lane. He just isn’t going to be that easy. Thinking about his career and that marathon run in Green Bay, the deep pathos of it that everyone who was following carries to some degree, remembering all of that will always dip you back, more than a little, into that well. It is almost too much.

Now that he’s finally on the ol’ riding lawnmower – the one that felt for so long so abstract, off in the distance of deep space, something to worry about some other season – I think I can look back at his career better, or can better try to, at least, with these valuable years of reflection under the belt. I think that Brett Favre reached his ceiling as a quarterback here. I do, for better and worse, because that’s who he was. There was never an “or.” He wasn’t going to ever not throw across his body, not throw up a prayer, not ignore everything but whatever was in his arm. He wasn’t going to ever not believe he could find a way to win, not be sure he’d avoid that sack, not escape danger of all sorts – or at least that was the plan. Whatever his ceiling as a quarterback could’ve been by changing any of those traits is not a ceiling – it’s a mirage, baking in the desert sun when you’ve already gone too far to go back, when you begin reimagining a different way.

Without question Favre took the Packers franchise collectively higher than ever imaginable. There was no way, before him, to know if they’d ever be that prominent again. Now there’s no way not to see that. Whatever his legacy is to you, it will be hard to think about. Hard to think about like anything that’s gone and meant a lot to you is. It wasn’t always easy following Favre. But adventures, usually, are good if you survive. And, well, here we are. We were pretty lucky to make the journey at all, and I think it’s important to remember as much of it as we can.

By the time he comes back to Lambeau Field it will be good to see him again, exactly as he is. There will be boos and there will be more cheers. Regardless of how long the team waits to do it, we won’t ever be able to predict exactly what’ll happen that day until it happens. There’s going to be some good and some bad, and it’s going to be memorable. All told, that sounds like a pretty good fit.

––

I remember wanting so badly for Aaron Rodgers to be good right off the bat. To silence the 4EVER segment of the fan population making his transition harder than it already had to be.

This hope, like going back to that time when Favre was starting, feels like a prehistoric thing to think about now.

The realest question to wonder about Rodgers now is whether or not he and the Packers will come close to maximizing his ridiculous talents. One Super Bowl title is a gift from the heavens, and his career will be one of the greatest this franchise or any other has seen if that’s where the total stands when it’s all over. But one title feels lesser than his skills, not exactly worthy of his talents. One Title walks into your local brewing company and asks for a Macro Light. One Title is Julia Louis-Dreyfus in a supporting role. One Title goes to Kroll’s and, have mercy on its soul, orders a salad.

The other thing about that question, though, is that while it’s certainly worth wondering whether or not Green Bay will get another title in this current era, I’m hoping to be doing that less so than I’ll simply be watching Aaron Rodgers play quarterback, expertly controlling this high-speed carousel of knives of an offense. This is what I’ve imagined the position could look like if I’d been anywhere near good at video games. Clinical, cold-blooded, cocky, and sure. This offense today is the offense I can’t wait to watch for, hopefully, many more years. When it’s rolling downhill there’s nothing more thrilling to join on the ride.

Clanging around in there, though, bouncing off the walls in our head like an empty aerosol can, is hope. And how can we not hope that all this talent turns into a little more than a fun ride? Into something more historic?

We’ll keep the knowledge in our back pocket, that wishing for Super Bowls is almost annually a disappointment. We’ll keep it there just in case. But with Rodgers at quarterback, don’t you believe there’s a chance that, every season, those 1 in 32 odds are still somehow in your favor? He doesn’t quite trick you so much as he makes you believe he can right enough wrongs to make anything work. Aaron Rodgers can make chance feel like a matter of time, deficiencies around him opportunities. But amid the points and the touchdowns and the execution, behind the daggers and darts and title belts, above the mantle of a still-unwritten legacy, the clock quietly keeps to itself, steadily ticking away.