Random Retrospectives: Don Hutson, Aaron Rodgers turn early season games into record-setting dominations

This story appears in the October 2014 issue of Packerland Pride magazine. Subscribe to the magazine here.

—

If not for being separated by 67 years, seven days, wave after wave of changes to the game of professional football, and oh yeah, also by position, Don Hutson and Aaron Rodgers could look at each of these stunning one-game career performances – each a stamp on and, in a pinch, encapsulation of a lot more than one game for these players; an option that could be thrown out when thinking about their respective mastery of a chosen spot on the field – and notice a bit of the other in them, like seeing a relative you didn’t know you had for the first time.

That’s a lot of qualifiers, though. So while Hutson and Rodgers both carved through and lit up October like a jack o’lantern with showings for the ages, each is abound with natural differences. Maybe we should go through them both.

Oct. 7, 1945. Sunday afternoon.

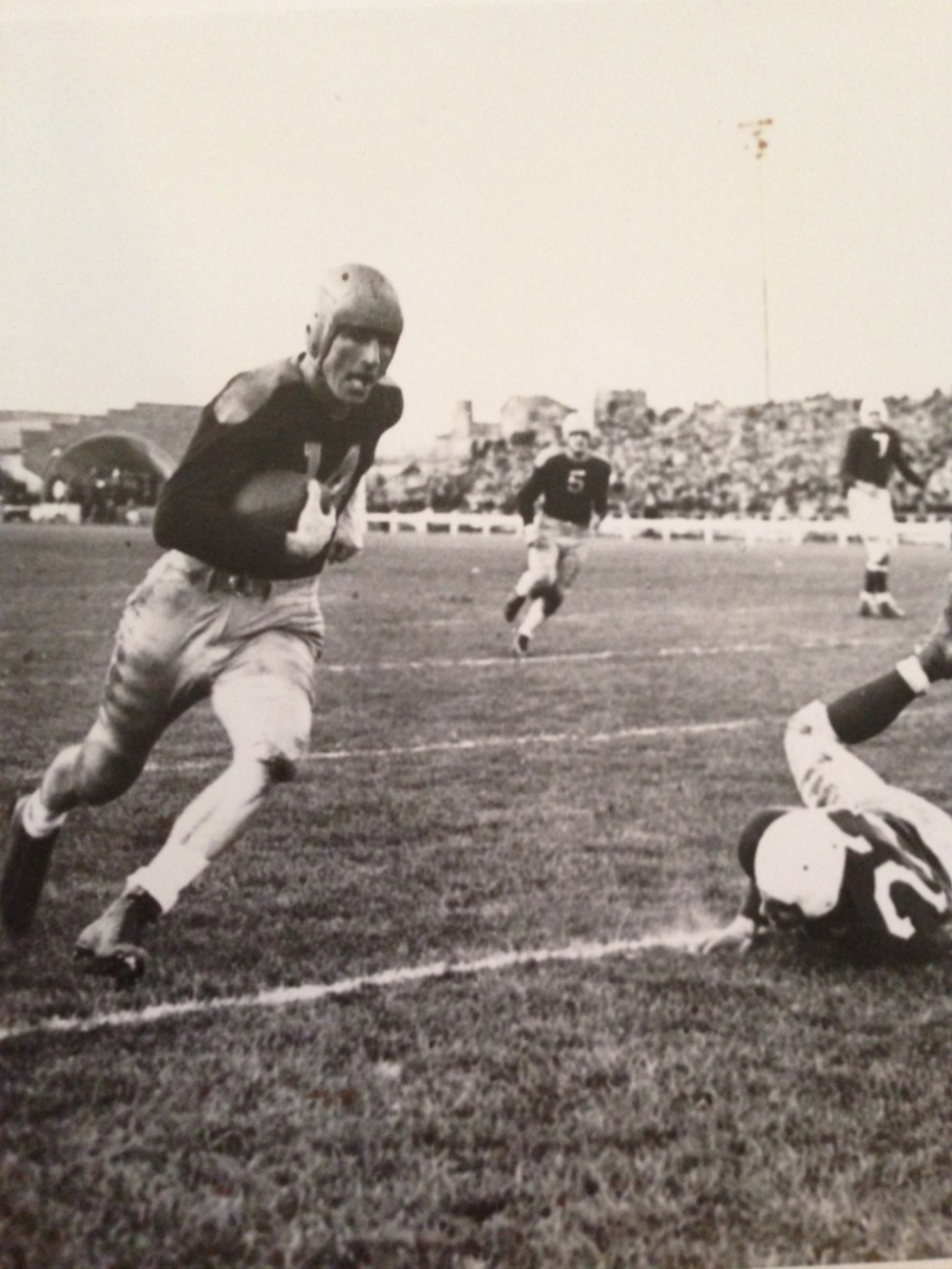

On the state fair park grounds in Milwaukee the wind was gusting. Don Hutson knew how to read the wind. He knew how to play it, had a good idea of how to adjust to the ball floating up in the current. He knew for a long time how to play wide receiver better than almost anyone else, long before the position was anything close to the norm it is today. He knew because he essentially invented most of its nuance.

But, according to Don Hutson, Don Hutson wasn’t supposed to be here anymore. After the 1944 season ended in another Green Bay championship, Hutson’s third as a Packer, he retired.

“If I ever play on the field again, I’ll jump off the Empire State building,” he said when announcing the end of his career.

Fast forward to late September 1945. The Packers notched a 31-21 opening day win over the Bears. Don Hutson kicked in four extra points. He should’ve been in a far different position than facing the 1-0 Detroit Lions on a blustery October day in Milwaukee the next week. But there he was, deciding to come back for a final season, in a final second week.

Detroit broke into the scoring column first on a seemingly-innocuous rushing touchdown early in the second quarter. Turns out that was the match hitting the trail of gasoline you see in the movies, the flames licking up the liquid on the concrete, climbing up the car and reaching the gas tank, then a quick pause and then – BOOM.

What happened starting after the Lions’ took that early lead were 15 of the most explosive minutes in league history. The highest-scoring single period ever by a single player in the NFL. Hutson scored 29 points by himself – catching four touchdown passes and kicking five extra points. Green Bay’s 41 overall points in the quarter remain tied for the most ever. By halftime, the score 41-7, Detroit’s opening touchdown looked like a counterfeit dollar drawn with crayons on construction paper next to a stack of hundreds.

First Hutson caught a 56-yarder from Roy McKay to tie the score. McKay, a halfback from Texas, threw four of the six total touchdown passes of his four-year career in this one game. Another back, Irv Comp, threw the next one, a 41-yarder to the superbly-named Clyde Goodnight, giving the Packers their first and last lead.

These were not long sustained drives for the most part. Three of Hutson’s four scoring catches came on the first or second plays of drives. Quick, lasting cuts into the Lions defense. Oliver E. Kuechle, filing his game report for the Milwaukee Journal the next day, said of poor, poor Detroit: “… the Lions were utterly helpless. They were trying to stop the unstoppable, and they knew it.”

The next one was a 46-yard pass and catch, McKay to Hutson, who would’ve had an even 30 points by himself for the quarter had Detroit not blocked the extra point on the ensuing score, a 17-yard pass from McKay to Hutson. Nothing is perfect, I guess.

Ted Fritsch made the rout worse for Detroit, bringing an interception back 69 yards for a touchdown and the score to 34-7. McKay hit Hutson a final time in the quarter for a six-yard score right before halftime, making it 41-7, Packers, at the break – everyone involved left equally stunned at how fast things had fallen out of control.

Hutson’s first half line: six catches, 144 yards, four touchdowns, a defeated, surrendered defense, zero care for strong Milwaukee winds, a notch in the belt for this whole passing game idea, a ticket stub worth saving. The game ended at 57-21.

Other records to tidy up from this game: The second quarter total of 48 is the highest scoring combined second quarter ever in league history, one point shy of the most for any quarter ever behind only a 28-21 frame put up by the Raiders and Oilers in 1963. The Packers’ total of 57 is still the most in team history. Hutson kicked two more extra points during the second half but otherwise didn’t play, possibly as a sign of mercy but also because when the work’s done, it’s done.

Hutson’s 31 total points were the most by one player in any Packers game until Paul Hornung broke the record on Oct. 8, 1961 – almost 16 years to the day Hutson set it – with four touchdowns, six extra points kicked, and a field goal, 33 points overall, against Baltimore.

Green Bay finished the 1945 season 6-4. It was Hutson’s last year in professional football, for real this time. It wasn’t a must-win. It didn’t come in a championship season. It was just an early stop on Hutson’s farewell tour. A big fat hint at the league’s future that Hutson was writing as he went. A game that lives without the barriers of time because in many way it’s still alive today.

Oct. 14, 2012. Sunday night.

Week 6. At 2-3, maybe it wasn’t quite a must-win yet. The Packers were coming off, simply put, just a real lousy loss to the Colts a week ago. It had everything: A sizable halftime lead blown, poor timing for a collective team sleepwalk again, a career-making scalding of the defense by one receiver (Reggie Wayne’s 13 catches, 212 yards, and a touchdown), injuries, and a missed field goal late. It was frustrating, basically Green Bay’s season up to that point, which saw alternating losses and wins, sparks of solid play smudged out by injury, inconsistency, and one Fail Mary.

Sunday Night Football was in Houston, Texas, that night, home of the then-undefeated Texans. This isn’t a new phenomenon, but there was some legitimate concern festering around the state of the Packers. A road meeting with Houston, its home crowd buzzing in anticipation at the sight of this weakened animal presented in front of them, looked, well, difficult is probably the best word for it. J.J. Watt was entering scary territory, and the offense, before Matt Schaub ate that poisoned apple or whatever happened to him, was built beautifully with Arian Foster running to set up Schaub’s throwing to the likes of Andre Johnson and Owen Daniels. They’d defeated Peyton Manning and the Broncos in Week 3 and were 5-0 for the first time in team history.

Hopefully that’s enough of a setup for you, because things are about to get progressively, historically, better from here.

Aaron Rodgers is probably going to put his name atop many categories in Packers record books. This one he had to steal back from his backup and friend, Matt Flynn. New Year’s Day 2012, Flynn memorably set the franchise mark for touchdown passes in a game with six in a wild win over the Lions. (Again: Sorry, Detroit.)

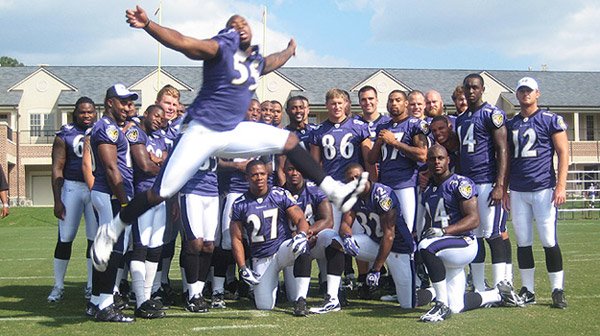

It was an insane game, but also largely meaningless. Later that calendar year, with a season spinning in place, Rodgers tied that team record against the Texans. Six touchdown passes, one deflated previously unbeaten squad torched at home, a postgame Shhh for the doubters later, and Rodgers had one of his finest games and one more top spot in Packers history. For Green Bay it was the start of a five-game winning streak and victories in nine of their final 11 games of the regular season.

Rodgers had lots of help that night, another reason why it is still so memorable. The Rodgers era has always been a beautiful partnership of precision quarterbacking and a deep, talented group of wideouts. In Houston that night, ridiculous touchdown catches came at an almost equal ratio to their passes.

After forcing a three-and-out to start the game, the Packers moved into Texans territory. They were just outside the 40 when Jordy Nelson caught one in stride down the right sideline, in a play eerily similar to the first touchdown of Super Bowl XLV, diving in for the first score.

The teams traded punts. Houston punted again, Green Bay’s defense stifling them early. On their next possession, inside Houston’s 10, Rodgers play-faked, bouncing around the pocket, finally flipping a pass to the right to James Jones. The ball was nosediving, and Jones had to circle around behind to get underneath it, making a fantastic diving bucket catch, managing to hang on through impact with the ground. It was 14-0 after a quarter.

The Texans started the second showing life, going 80 yards for a score. After three completions and a pass interference call, the ensuing drive ended with Rodgers zipping a touchdown to Nelson on a textbook 21-yard post in the end zone.

Up 21-10 in the third Mason Crosby tacked on a 39-yard field goal, but Houston extended the drive after Connor Barwin was flagged for jumping on a teammate trying to block the kick. Another Houston penalty gave Green Bay another chance later in the drive, which probably would’ve ended in another field goal try. This time they paid for it. From the 1, Rodgers threw a dart to the back right corner of the end zone, where Nelson, wearing a defender like a cape on his back, somehow came down with the grab. Seriously: You really don’t throw six touchdowns without some help, but these throws-and-catches were not normal by any standard.

Green Bay started the fourth with the ball up 28-17. Third-and-1 from the Texans’ 48, Houston, trying to crawl back into the game, sent the house. Rodgers play-faked and had serious pressure in his face upon turning around. Rolling to his right, he waited as long as possible, throwing a bullet as he was pile-driven into the turf to Tom Crabtree, who released on his block, snuck behind a secondary playing up close to the line, and was wide open in the seam when the ball hit him. He strode the final 30 or so yards in for the backbreaking score.

Sam Shields intercepted a low comeback on the second play of Houston’s next drive. The wheels were coming off. Following three straight runs, Rodgers got number six. From the Texans’ 18 he lobbed a perfect spiral into the right portion of the endzone. James Jones was not open, mind you – in fact, his defender was directly between him and the ball coming down. But Jones, crafty as ever and athletic as hell, reached his right hand around the corner, tipping the ball enough to give himself time to corral it, juggling the pass before bringing the touchdown in on the fall. It was the night’s most incredible catch, saved for the record-tying last. The Packers won by a symmetrical 42-24, evening up to 3-3 for the season. Rodgers completed 24 of 37 passes for 338 yards, six touchdowns, no picks.

It wasn’t necessarily that it happened. Envisioning Rodgers throwing six touchdowns in a game isn’t difficult. It was when and where and how it happened.

When, as they were down in an early season valley – and not their first of the year – that had many questioning where the heck this season as a whole was going. Where, in a loud Houston thunderdome against an undefeated contender at the time. And, lastly and most impressively, how – because of how clinically and matter-of-factly this ravaging of the Texans was performed. It was a statement in that it was handled like business as usual, like the team was saying, “What else did you expect, people?” Rodgers’ shush in the postgame interview on the field served this notion, calming everyone with concerns down, big-time, for a night or two.

These performances by Rodgers and Hutson were different in many ways. What made me think about them together, though, is the cold-blooded brilliance. Their respective teams needed them, to be sure, but in many ways, in the grand scheme of things, these were just two regular games on the broad spectrum of other Packers all-time classics. That these two conjured up such greatness on some October Sunday, that they’re still worth remembering now, is exactly why I remember them. The best part about games like these is never knowing when they’ll strike.