The waking of a sleeping giant: The Hotel Northland returns to downtown Green Bay, where it never really left

This story appears in the March-April 2015 issue of Packerland Pride magazine. Subscribe to the magazine here.

—

The Hotel Northland was dead before it was alive. Remember that when you start reading the stories about the new boutique hotel coming to Green Bay; seeing the activity that hovers around a construction site, when something is going up. It never went down, mind you, and wasn’t supposed to ever die. But it did. And when it did, remember that it was never going to return to what it was. If anything at all.

Remember that the Hotel Northland was gone. Buried in the folklore of how it used to be. What it used to mean.

Before the funeral there was no building in Green Bay more alive. No one place more synonymous with the Glory Years. And before those, the national ascendance of Green Bay and the Curly Lambeau-led Packers. If you asked for a physical definition of what the city of Green Bay was like for decades, what it is striving to be again, you would probably get something that looks a lot like the Hotel Northland. For more than 50 years, when the city’s downtown district was at its peak in prominence, humming with life day or night, the Hotel Northland on the corner of Adams and Pine was its beating heart.

The Northland is a landmark for history that either passed through Green Bay or stayed awhile longer. It hosted the National Football League’s annual conference in 1927. It served as the league’s headquarters when Green Bay hosted NFL Championship games in 1961, 1965, and 1967. Vince Lombardi held his introductory press conference in a room there on February 3, 1959. It welcomed First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy and Jacqueline Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, and Richard Nixon as well as other politicians, and actors in their prime.

Try to remember all that sometime later this year, likely in the fall – football season – when the Hotel Northland will open again. Because when it does, it opens new. But it also opens history. If all goes according to plan it will be that landmark again.

–––

It isn’t normal to get the chance to re-enter a place with such significance to Green Bay and the Packers. Especially a building that died once already.

Normal would be tearing down a building and leaving an open space for lease. Normal would be to move on from the past. But the Northland was never opened to be normal in the first place: It was supposed to be better. It altered the landscape of the city. With a place so interwoven with Packers history, and with Packers history so wrapped into the present, the Northland will almost certainly impact the future of the city in major ways. The final answer to that is far away yet. It will depend on the new Northland’s resurrection into something like its old self.

This is a comeback story for a place that shouldn’t need an introduction.

–––

Of course a building can’t live, it can’t have a heart to beat, without actual people pulling the strings. When asked what the Hotel Northland’s comeback story means to her, Victoria Parmentier’s face lights up.

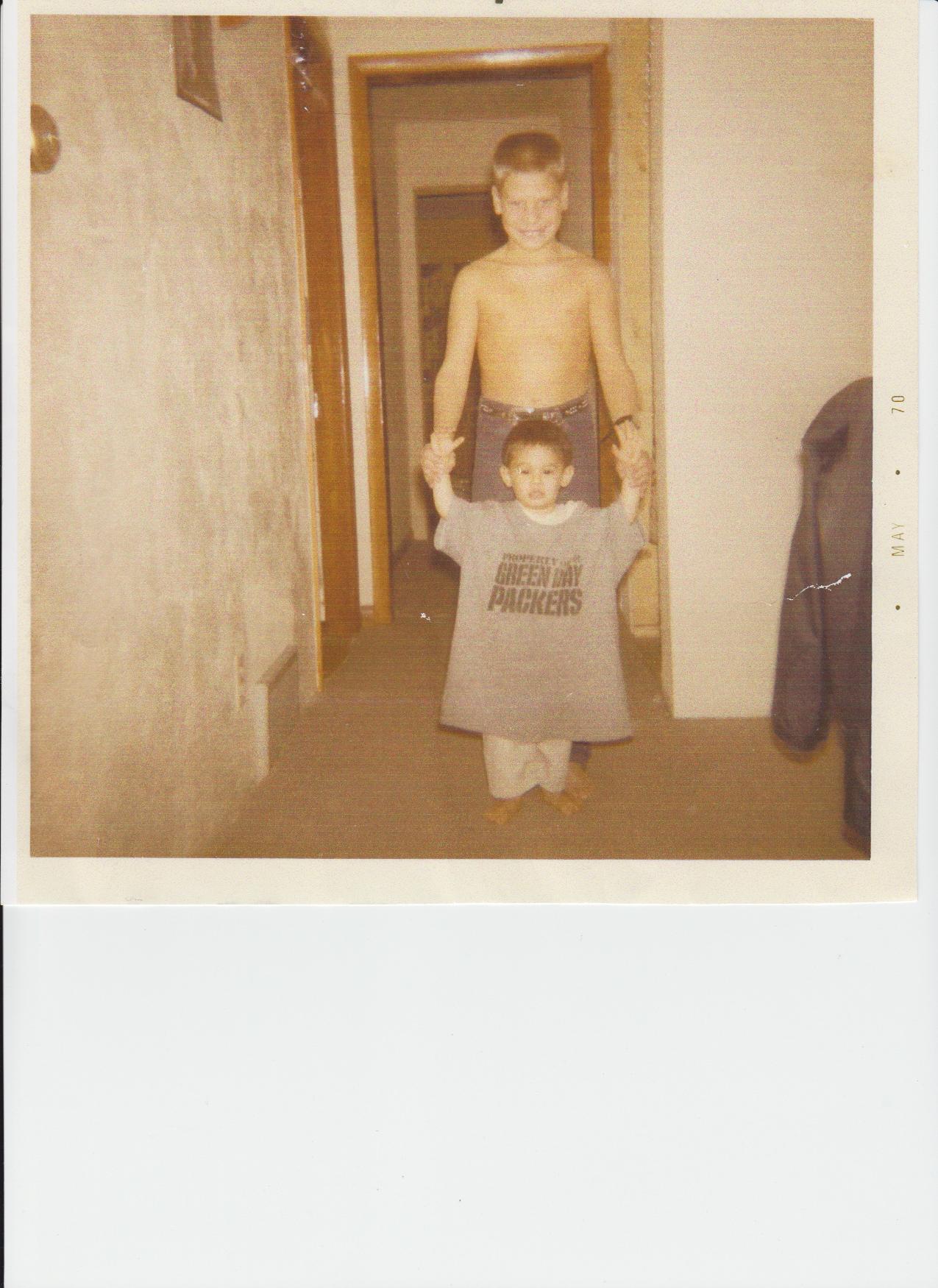

In 1973 Parmentier responded to an ad in the paper and started working at the Northland. She usually worked behind the front desk. But at the Northland you did everything. She worked at the street level coffee shop when needed, or up on the top floor in the circus club bar, mixing brandy and sodas – for any other cocktail she’d have to ask for the ingredients. Shortly after starting at the hotel, Victoria also began living there. She was crowned Miss Green Bay in March 1974 when she was 20. When it was time to leave her celebration that night in the Northland’s Crystal Ballroom, Victoria simply went upstairs.

Parmentier’s life has continued and grown with the Northland since then. She has a grandfather clock from the hotel in her home. And she plans to return it to the hotel when it re-opens. She has other small mementos – postcards, cups, Schroeder Hotel dinnerware that she gives away as gifts.

“I think it’s going to be fantastic,” Parmentier says of the new hotel.

She is standing in the Northland’s lobby, leaning against the front desk she used to work behind. She remembers the old register; how, if you made a mistake while punching out a bill you’d have to take the paper out and re-insert more. It was not a fun process. Going through old customer cards we find in the building’s basement she remembers some names, even details about people who checked in and out long ago. She knows every nook and cranny of the building. Instinctively pointing out where to watch your head, where the light switches are, where the new came in, the old remains.

And what it looked like as a flowing, living, hotel.

–––

By the late 1990s the Port Plaza Mall in downtown Green Bay was suffering. In 2001 it became Washington Commons, a last shot at making the space a mixed use facility of commercial space, offices, and shops. In 2004, already hemorrhaging tenants, ownership of the building went back to the city. In 2012, after about six years of sitting vacant and closed, the mall was demolished.

As a seasonal employee for the City of Green Bay, working a few summers while the mall was empty, an eyesore, I had to go inside every so often for maintenance. We went through an unmarked door in the back, through administrative offices, flashlights beaming layers of dust in the pure dark. Then you made it to daylight breaking through the glass roof of the common area: The escalators on the first level, half-broke store signs, debris and broken light bulbs littering the floor. Old plastic Christmas decorations stored away. It was spooky in there, a sad and all-too-obvious symbol at the time for downtown’s general feeling of decay. Signs of life – once filling the mall like pennies shining in the pool under the gushing water fountain – were gone. There were attempts to save it, but the mall was left behind. By the time the building went down, even those nostalgic for what it was at its best knew it had to go.

The corporate headquarters of Schreiber Foods is now in its place. The building is modern. At night it glows different colors – green, purple, gold. It adds life, a lighthouse of sorts, for the area. It is the future, an anchor of the new downtown. Even while it was still standing, the mall was in the past.

Sometimes history is history for good reason.

–––

Parmentier’s connection with the Northland was getting stronger as the rest of the city was slowly forgetting about it.

That was when the mall was bustling, before anchor stores left, leaving unfixable holes. In 1972, Robert Safford, president of First National Financial Corporation, which owned a chain of banks around northeast Wisconsin, bought the Bellin Building – another uniquely unchanged structure in downtown Green Bay, built in 1915 – and the Hotel Northland. Safford ran the Northland as a hotel until 1980. The following year, falling on hard times, the public gradually avoiding downtown more and more, the Northland died.

The building remained – one of the crucial reasons it can be restored today. But hotel rooms were converted into one-and two-bedroom apartments, kitchens and new bathrooms were installed, and the Hotel Northland became the Port Plaza Towers, 100 percent of its use now for low-income housing for the elderly and disabled.

It changed in those days. The magnificent Crystal Ballroom was used as a rec room; plain wooden tables and board games covering the floor. It was this or that to those around town, but not a hotel anymore. It was largely looked over, forgotten to an extent like most of the area eventually was. We just don’t go down there anymore became a common line concerning downtown.

But the building was never left behind. It never succumbed to the mall’s eventual fate. The Northland’s grasp on the city, on people like Parmentier, was still holding on. That hold became the pull giving the building a chance at getting back what it was – a hotel.

But the Northland wouldn’t be coming back – almost certainly not as soon as this fall – if it weren’t for a terrible summer seven years ago.

–––

In June of 2008, flooding in southern Wisconsin became a devastating, large-scale disaster. On June 9, a federal state of emergency was declared in 30 Wisconsin counties: Essentially its entire lower half from the base of the state’s geographical thumb on down. The state received sizable tax credits to help recovery efforts, some of which filtered into the Low Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) Program, a federal subsidy that awards money to go toward the construction of low-income rental homes and properties.

The short version goes like this: The federal government divvies up an available amount of tax credits, which a given state then has two years to award to individual projects. Projects from developers are judged against other proposals, scored, then awarded. It’s meant to be a competitive environment. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development states major factors under consideration include plans that “serve the lowest income families” and those that are “structured to remain affordable for the longest period of time.”

From 2009-2010, two years after the floods, applications for projects totaled about $183 million in the LIHTC program alone. In 2009, the first carryover year following the flooding, the total was just under $95 million. In contrast, once those tax credits went away in 2011, only $37.6 million in LIHTC credit applications was received.

Again, the LIHTC program was just a slice of the overall tax credit pie, but developers used the influx of potentially-available money to cash in, getting projects off the ground.

Which brings us back to the old Northland building. The Port Plaza Towers were being run by RE Management, Inc., a Green Bay-based company specializing in affordable housing and living complexes for seniors and people with disabilities.

And Victoria Parmentier, RE Management’s president who shifted into real estate in ‘81 but never completely away from her old home at the Northland, saw a window of opportunity.

At the time, 147 apartments were in use at the Port Plaza Towers. With nowhere to move their occupants, RE Management could do nothing to make the building available for potential investors. They could want and hope, but any real change was limited to an indefinite waiting game. There’s a strong chance there’d still be no progress – as far as a new hotel is concerned – without the LIHTC tax credits in the two years following the summer of 2008.

But while there was more of that money available in 2009, any proposal still had to win on its own merit.

It did. Back in 2000, Safford sold the Towers to the non-profit Wisconsin Housing Preservation Corporation, based in Madison. They submitted the LIHTC proposal, and with RE Management’s history in their areas of expertise aiding the application, the corporation received a chunk of the $43.5 million awarded (of around $95 million in applications) in LIHTC credits in 2009.

In 2010, the Woodland Park and Trail Creek apartments – 150 total units of senior housing – were built. And after an insanely busy summer of 2011, moving people from their old apartments into new ones in literally a day – tenants drawing desired floor plans for workers who packed, moved, then unpacked and arranged new homes for about 6-8 people per day – all of the Port Plaza Tower’s previous tenants had new homes either in these apartments or elsewhere.

Parmentier’s company has presided over the empty building since. The forward momentum a new Northland needed was now put in motion. Now there was a pace, a moving timeline for the future.

–––

Last summer, Gov. Scott Walker signed an historic tax credit bill opening up tax credits for historic preservation projects. For the Northland these were essential in keeping the ball rolling forward. Last fall the project received a loan guarantee from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Along with the protective layers set up by the city, and with additional funding streams secured, the hotel, the thought of it in use, was really real again. The Northland had its long-awaited chance.

Green Bay’s “$1 million hotel,” as it was nicknamed when it first opened, is going to need a little more than that this time around: More than 40 times that. Steven Frantz, the Northland’s asset manager and VP of sales – from Frantz Community Investors, the Cedar Rapids, Iowa-based group that will develop the new Northland along with KPH Construction – said in February the project will cost $44 million.

But the loans and additional funding mean luxury. The aim is for it to be the premier hotel north of Milwaukee. And the historic tax credits ensure that high-end must mix with old-fashioned appeal: The reasons the dream of bringing back the Northland never completely evaporated. In short, the Northland has to be what it was. Then it has to be better.

The governor signed the bill last summer, making available tax credits the project couldn’t do without, in the lobby of the Hotel Northland.

–––

When Walter Schroeder built the Northland, adding to his chain of Wisconsin lodgings – the Hotel Loraine in Madison, Hotel Astor in Milwaukee, and Hotel Retlaw (Walter spelt backwards) in Fond du Lac are some of his other noteworthy places – he had a vision of what Green Bay would become. And what it ultimately became with his hotel at the center.

Schroeder hired Milwaukee architect Herbert Tullgren for the design. In March 1924, the nine-story, 300-room Tudor Revival style hotel opened. It was dubbed Green Bay’s “$1 million hotel” not just because it was the biggest or best in the city – though it was both – but a million bucks is actually what it cost to build. The March 20, 1924 issue of the Green Bay Press-Gazette said the hotel “marked an epoch in the city’s history.” Another article later called it “one of the most important places in the city, not only as a business house but as a social center.”

The Northland’s exterior looks about the same as it did on opening night. Nine floors of rich brown brick outlined with limestone and cream-colored stucco. Windows and design simple and symmetrical, the U-shaped building – the northeast wing was built in 1947 – looks like a perfect square at its front-facing intersection. The main entrance on Adams used to have a sign, now an empty marquee. There’s another, smaller, one over the Pine Street entrance, where there’s a “Smile, you’re on camera” sticker on the glass door. The building has an imposing presence, a sense of weighty substance. And yet it’s easy to not see the Northland if you’re not in its immediate vicinity, or too-used to the surrounding layout. It stands quietly. There haven’t been many reasons in past years to head towards that particular area in downtown Green Bay. It is across the street on Pine from the downtown YMCA, an original building with similar ties to days gone by.

The hotel sits on the end of Adams Street, once one of Green Bay’s major downtown arteries. The Northland was an anchor. Other hotels, bars, restaurants, high-end clothing stores, Don Hutson’s Playdium bowling alley – they all once called Adams home. Today it is slowly climbing out of its doldrums. A coffee shop recently opened right across the street from the Northland, perhaps getting a jump on the anticipated foot traffic. In too many storefronts in the immediate area, though, the only signs in the window still read something along the lines of For Rent.

Adams is, for now, the quieter off-street to parallel-running Washington one block closer to the Fox River. When the Northland was alive, Adams Street was the polar opposite of quiet.

–––